3. Tic-Tac-Toe

Worth: 5%

DUE: Monday November 3, 2025 at 11:55pm; submitted on MOODLE.

Files:

asn3.ipynb/asn3.py

3.1. Task

The time has come to make one of the best video games of all time — Xtreme tic-tac-toe. It’s effectively tic-tac-toe except the game sizes can differ. Your task is to implement the game, from the ground up, entirely.

You will

Write functions to setup the initial game board

Read and validate moves from players

Apply moves to the game board and check for winning conditions

Render and display the game board

Implement the game loop

3.2. Provided Files

You are provided with

A notebook file called

asn3.ipynpcontaining the starting point of the assignmentThis file is to be uploaded to Google Colab

This notebook contains the function definition lines with docstrings and

asserttestsThe notebook also includes a special if statement

if __name__ == "__main__":at the endThis is included to help with marking and unit tests

More details on this line are provided below

Alternatively, if you prefer to complete the assignment with an IDE on your own computer, you may download and use the

asn3.pyfile

Warning

Do not alter the function details in the provided .ipynb/.py files

Do not change the name of the functions

Do not remove the function description

Do not remove or add to the parameter list

3.3. Part 0 — Read the Assignment

Read the assignment description in its entirety before starting.

3.4. Part 1 — Uploading Files to Colab

After downloading the notebook file above, you will need to upload it to Colab to get started. See the respective section from assignment 1 for an example on how to do this. I recommend saving a copy of this notebook file to your Google drive and then work with that one. You don’t have to, but you will have to re-upload the project every time you want to work on it.

3.5. Part 2 — Setup Game

The tic-tac-toe game board is to be represented as lists of lists of strings where the strings may be a " " (space),

an "X", or an "O". For example, an empty 3x3 game board would be

[[" ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " "]]; however, one can think of this list of lists as a

two-dimensional matrix

[[" ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " "]]

where the first index would be the row and the second is the column. With this configuration, the top left corner of the

game board would be at index 0, 0. In this example, if the list of list was referenced by a variable named

board, then board[1][2] would be the last element in the middle row.

A 3x3 board was shown in the above example, but this is Xtreme tic-tac-toe, which means the game can be of arbitrary

size. Thus, we may have game boards that are 3x3, or 4x4, or 999x999. If the game board was specified to be 4x4, we need

a list of 4 lists that contain 4 strings —

[[" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "]], or as a matrix

[[" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "], [" ", " ", " ", " "]]

Write a function setup_game that takes an integer representing the desired board size as a parameter and returns the

appropriate list of lists of strings representing the game board.

Remember, we need to ensure our lists are in fact separate lists and not simply aliases to the same single list. If we

specified a game board size of 3, we need a list containing three references to three separate lists, not three

references to the same single list.

3.6. Part 3 — Parse Move

All moves a player makes will be entered as a string in the form "x, y", where x is the column and y is the

row. However, the game needs the move to be two separate integers in order to effectively use the information.

Write a function parse_move that takes a move string as a parameter and returns a tuple of the integers representing

the x and y coordinates of the move. For example, calling parse_move("2, 1") would result in the tuple

(2, 1) being returned.

3.7. Part 4 — Validate Move

Player moves are considered valid if (a) the specified game board cell/location is unoccupied (contains a " "

(space) character) and (b) is within the game board.

Write a function is_move_valid that takes a move tuple and the current game board as a parameter and returns a

boolean indicating if the provided move is valid — True if it is valid, False otherwise.

For example, consider the current game board being board = [["X", " ", " "], [" ", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]].

is_move_valid((2, 2), board)returnsTrueis_move_valid((2, 1), board)returnsFalsesince(2, 1)already contains an"O"is_move_valid((-2, 1), board)``returns ``Falsesince the move location does not exist on the provided game board

Note

When thinking of the game board like a matrix, there is no rule indicating which index of a list of lists is the row

and which is the column. In other words, there is no rule saying that the indexing is board[row][column] or

board[column][row]. However, for this assignment, we will have the first index be the row and the second be the

column.

Since we like to follow the conventional cartesian coordinate system of x specifying the horizontal positioning

— the column — and y specifies the vertical positioning — the row, we must be mindful of how we use these

values to index the board. By following this convention, it would mean that one needs to index the board with y

first to specify the row and then once the row is selected, the x value is used to indicate which column in the

row the cell/location is. In other worse, the correct indexing would be board[y][x].

3.8. Part 5 — Apply Move

Once a move is provided, parsed, and validated, the move can then be applied.

Write a function apply_move that takes an already validated move tuple, the current game board, and a string of the

current player’s symbol ("X" or "O"), and returns a new game board with the player’s move applied. For example,

if one called apply_move((0, 1), [["X", " ", " "], [" ", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]], "X"), the function would

return the new list of lists of strings [["X", " ", " "], ["X", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]].

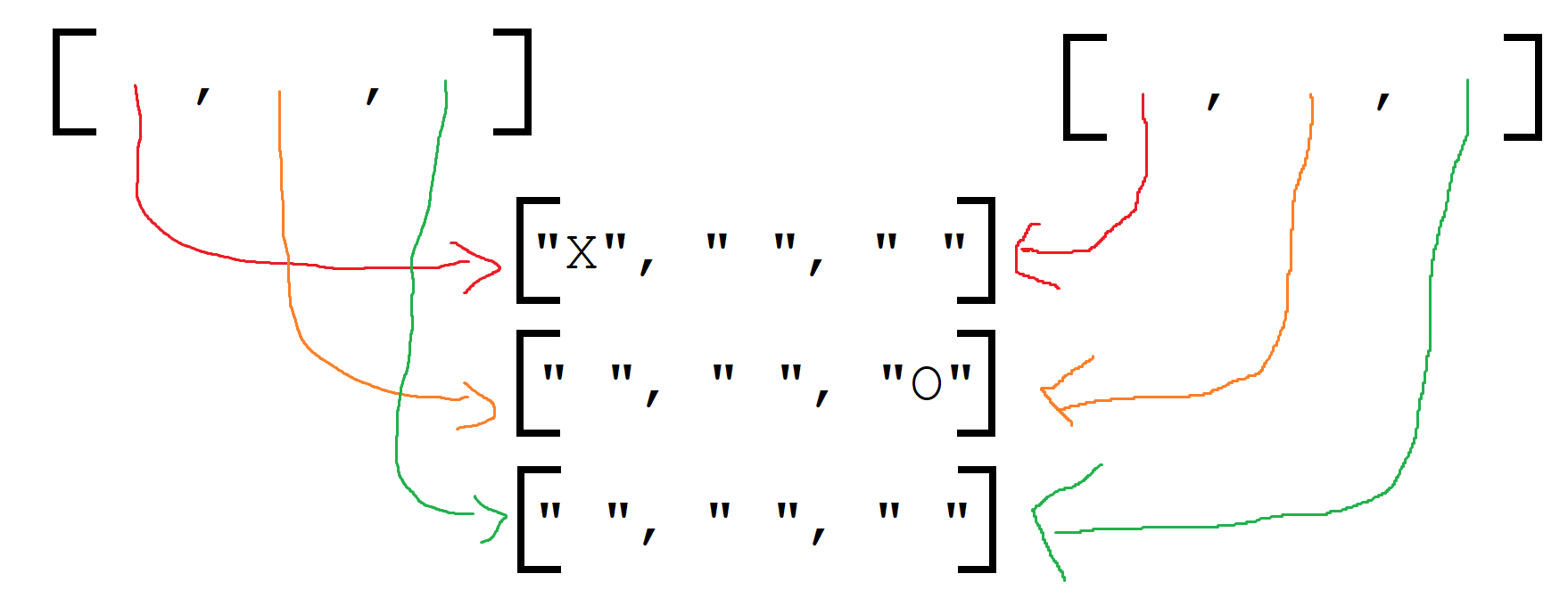

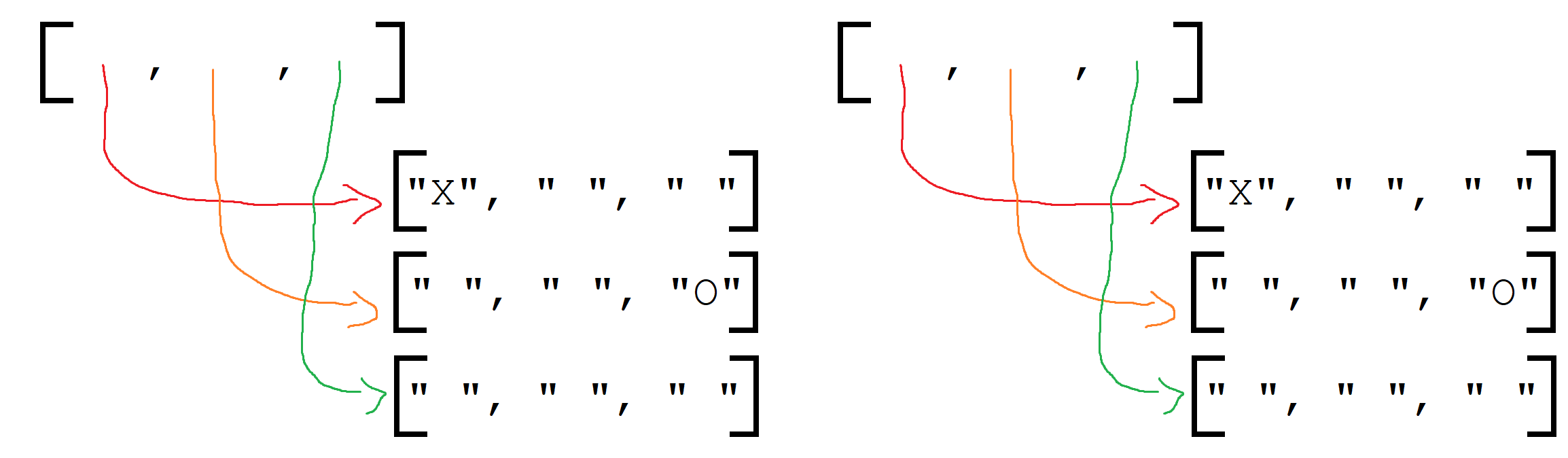

This function should not have any side effect — the game board passed as a parameter to the function should not be altered in any way. Instead, a copy of the game board is to be created that is then modified and returned by the function. Be warned, however, that one needs to be careful how they perform the copy — when we have a list of lists, we really have a list of references to other lists; we need to ensure we are making copies of the internal lists and not just the outside list. If we perform a copy naively, we may accidentally make a copy of the list with copies of the references — this is called a “shallow copy”. Refer to the following images to see the difference between a “shallow” copy and a “deep” copy in this context.

Example of a “shallow copy” — only the references to the internal lists were copied. The actual internal lists were never copied.

Example of a “deep copy” — copies of the internal lists were made.

3.9. Part 6 — Check For Winner

A player wins the game if they meet one of the following conditions:

They occupy all cells in a given row

They occupy all cells in a given column

They occupy all cells in the top left to bottom right diagonal

They occupy all cells in the bottom left to top right diagonal

All of these conditions need to be checked in order to confirm if someone has won or not.

3.9.1. Check Row & Column

The process for checking the row and column conditions will be very similar.

Write a function check_row that takes the current game board, an integer representing a specific row to check, and

the player’s symbol as a string as parameters, and returns True if the specified player occupy all cells in the

specified row and False otherwise. For example, if board = [["X", "O", "O"], [" ", "O", "O"], ["X ", "X", "X"]],

calling check_row(board, 2, "X") would return True.

Similarly, write a function check_column that takes the current game board, an integer representing a specific

column to check, and the player’s symbol as a string as parameters, and returns True if the specified player occupy

all cells in the specified column and False otherwise. For example, if

board = [["X", "O", "O"], ["X", "O", "X"], ["X ", "O", " "]], calling check_column(board, 1, "O") would return

True.

3.9.2. Check Diagonals

Write a function check_down_diagonal that takes the current game board and the player’s symbol as a string as

parameters, and returns True if the specified player occupies all cells in the downward diagonal starting in the top

left, and False otherwise. Unlike the rows and columns check, there is only one downward diagonal starting in the

top left, thus there is no need to include an integer as a parameter.

Similarly, write a function check_up_diagonal that takes the current game board and the player’s symbol as a string

as parameters, and returns True if the specified player occupies all cells in the upward diagonal starting in the

bottom left, and False otherwise.

3.9.3. Checking All Directions

Write a function check_for_winner that takes the current game board and the player’s symbol to check as a string as

the parameters, and returns True if the specified player has met any win condition, and False otherwise. This

function will make use of the check_row, check_column, check_down_diagonal, and check_up_diagonal

functions described above.

3.10. Part 7 — Rendering the Game Board

Currently the game board is represented as a list of lists for Python, however this representation is not ideal for humans; typically humans represent tic-tac-toe as a grid. For example, consider the following empty 3x3 game example:

| | -+-+- | | -+-+- | |

In the above example, since it is an empty board, each cell is an empty space and the cells are seperated by horizontal

(-) or vertical (|) lines. Intersecting lines are drawn as plus signs (+).

Below is an example of a game board with player moves applied:

X|O|O -+-+- |X| -+-+- X| |O

The above example shows how player symbols ("X" or "O") are to be displayed in the game board.

A function needs to be written that will take the encoding of the game board as a list of lists of strings and return a human friendly string that can be displayed.

Write a function render_board that takes the current game board as a parameter and returns a string representing the

entire board. This function will include all horizontal (-) and vertical (|) lines in addition to the

intersecting symbol (+).

Given board = [["X", " ", " "], [" ", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]], calling render_board(board) would return the

the following string "X| | \n-+-+-\n | |O\n-+-+-\n | | \n", which would be printed out as the following:

X| | -+-+- | |O -+-+- | |

Before starting to write the function, consider the complexity of what is required. The whole board has many cells, each cell will have different symbols, and further, each cell has different separation symbols.

If, on the other hand, it were possible to break the problem down such that there was a mechanism to render a whole row,

then the complexity in render_board feels much lower — no need to think of the details of rendering the individual

cells, just render rows with horizontal lines between them.

3.10.1. Render Row

Write a function render_row that takes the current game board and a specific y/row value as parameters and returns

the string representation of the specified row. This function will include the vertical lines (|) within the string

being returned along with a new line character at the end.

Below are examples of using the function with board = [["X", " ", " "], [" ", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]]

render_row(board, 0)returns the string"X| | \n"render_row(board, 1)returns the string" | |O\n"render_row(board, 2)returns the string" | | \n"

Once again, however, one may feel that the complexity of rendering a whole row to still be rather complex. Instead, if a function to render individual cells existed, then that portion of the rendering can be offloaded.

3.10.2. Render Cell

Write a function render_cell that takes the current game board and the x/column and y/row coordinate of the cell

from the game board to be rendered. This function will return a string of the contents of the specified cell. This

function will only include the cell contents in the string and not any horizontal (-) or vertical (|) lines.

Below are examples of using the function with board = [["X", " ", " "], [" ", " ", "O"], [" ", " ", " "]]

render_cell(board, 0, 0)returns the string"X"render_cell(board, 2, 1)returns the string"O"render_cell(board, 0, 2)returns the string" "

3.10.3. Putting it together

Once both render_row and render_cell are complete, write the render_board function described above. This

function will make use of render_row, which in turn will make use of render_cell.

3.11. Part 8 — Putting it Together

The main game loop is now needed. More accurately, we need the setup for a game, the game loop, and the displaying of the final result. Fortunately, with all the core functionality already written, much of this is just a matter of putting things together.

The setup is fairly straight forward:

Prompt the user for the game size

Create the game board with the specified size

Setup some bookkeeping variables

Move counters

Current player symbol

A flag for if the game is over

The game loop is going to do much of the work. It needs to:

Run while no one has won yet and there are still valid moves left

Set the current player symbol

Render and display the board

Display the current move counter

Prompt the user for a move until they provide a valid move

Apply the move to the board

Increase the move counter

Check for a winner

Once the game ends, final details need to be displayed to the players. This will include:

The final game board

Say who won the game and in how many moves or state that it’s a cat’s game (which means no one won)

Some additional things to note about Xtreme tic-tac-toe:

X always goes first

The game can end in a draw if there are no more valid moves available (this is called a “cat’s game”)

X will always win a game that’s smaller than 3x3 (think about why that is)

Below is some pseudocode that you may find helpful. For the most part, it is just restating the above points. The first

line of code, the if statement, is not actual pseudocode and is something you need in your code. It is required for

our marking and basically means that the code within the block will only run if we are directly running this script. For

example, if one were to import your code into another script (which is done for marking), Python would try to run

all the code within the imported script. By having this line of code, it says to not bother running the block unless the

script was ran directly.

# Not actual pseudocode --- makes it so the import

# from the unit tests do not break things

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Setup code

Get the game size

Create a game board of the size

Initialize a move counter

Set current player symbol

Set game over flag to false

# Game loop

while the game is not over

Set current player symbol

Render and display the game board and move counter

Read input from the user until valid input is entered

Apply the move to the game board

Increment move counter

Check if player has won

# Game ending part

Render and display the game board

Print out which player won and in how many moves or if no one won

Below is an example of a full game with player "X" winning. Notice that player "X" entered an invalid move for

their first move.

Game Board Size: 3

| |

-+-+-

| |

-+-+-

| |

Move Counter: 0

X's move (x, y): 1, 3

INVALID MOVE --- TRY AGAIN.

X's move (x, y): 0, 2

| |

-+-+-

| |

-+-+-

X| |

Move Counter: 1

O's move (x, y): 1,1

| |

-+-+-

|O|

-+-+-

X| |

Move Counter: 2

X's move (x, y): 0,1

| |

-+-+-

X|O|

-+-+-

X| |

Move Counter: 3

O's move (x, y): 1,0

|O|

-+-+-

X|O|

-+-+-

X| |

Move Counter: 4

X's move (x, y): 0,0

X|O|

-+-+-

X|O|

-+-+-

X| |

Player X won in 5 moves.

Remember, it is possible for a draw. For example, if on a 3x3 board, all 9 cells were occupied and no one has met any win condition, then the game is a draw, which is often called a “cat’s game” in tic-tac-toe. Below is an example of the end of a game with a draw.

X|O|O

-+-+-

O|X|

-+-+-

X|X|O

Move Counter: 8

X's move (x, y): 2,1

X|O|O

-+-+-

O|X|X

-+-+-

X|X|O

Cat's game; no one wins.

3.12. Part 9 — Testing

To help ensure that your program is correct, run the provided assertion tests. Each function is followed by a series of

commented out assertion tests that will help you test your code. When you are ready to test your functions, simply make

them not comments (remove the #) to include them in your running program. There is no guarantee that if your code

passes all the tests that you will be correct, but it certainly helps provide peace of mind that things are working as

they should.

There are no assertion tests for the final game loop, so you will need to run the game in order to get a sense of if it is working or not. When testing by playing, actively try to break the game.

Realistically you should have been running tests after you complete each of the above parts, but this part is here to remind you. Remember, we are lucky that we get to test our solutions for correctness ourselves; you don’t need to wait for the marker to return your assignment before you have an idea of if it works correctly.

3.13. Some Hints

Work on one function at a time

Get each function working perfectly before you go on to the next one

Test each function as you write it

This is a really nice thing about programming; you can call your functions and see what result gets returned

Mentally test before you even write — what does this function do? What problem is it solving?

If you need help, ask

Drop by office hours

3.14. Some Marking Details

Warning

Just because your program produces the correct output, that does not necessarily mean that you will get perfect, or even that your program is correct.

Below is a list of both quantitative and qualitative things we will look for:

Correctness?

Did you follow instructions?

Comments?

Variable Names?

Style?

Did you do just weird things that make no sense?

3.15. What to Submit to Moodle

Make sure your NAME and STUDENT NUMBER appear in a comment at the top of the program

Submit your version of

asn3.pyto MoodleDo not submit the .ipynb file

To get the

asn3.pyfile from Colab, see the example image in Assignment 1

Warning

Verify that your submission to Moodle worked. If you submit incorrectly, you will get a 0.