15. Tuples, Dictionaries, and Sets

In addition to lists, there are a few other noteworthy datastructures we will look at in this course

Although they will not be used as much as lists, it’s important to be aware of the tools you have at your disposal

15.1. Tuples

A tuple looks and behaves similar to a list, but has slightly different syntax

Tuples use parentheses

(,)

1some_tuple = (10, 11) 2print(some_tuple) # Results in (10, 11)

They are both ordered sequences of data

They can be indexed like lists

1some_tuple = (10, 11) 2print(some_tuple[0]) # Results in 10

But unlike lists, tuples are immutable

Once they are created, we cannot change them

They’re ideal for when we need to pack some data together

For example, a tuple would be great for storing cartesian coordinate

(x, y)Tuples were also used in the Starbucks assignment to store the latitude and longitude pairs

1for row in starbucks_file_reader: 2 location_tuple = (float(row[0]), float(row[1])) 3 starbucks_locations.append(location_tuple)

15.2. Dictionaries

Dictionaries are amazing data structures that are a little more complex than lists and tuples

Much of their complexity is hidden from us so we will not worry about it here

Simply, they are like list that you could index with strings, or various other types, instead of just integers

Consider the following example of storing grades for students

1# Create a new, empty dictionary

2some_dictionary = {}

3

4# Add a few things to the dictionary

5some_dictionary["Billy"] = 74

6some_dictionary["Sally"] = 88

7some_dictionary["Jimmy-Bob"] = 99

8

9# Print out the dictionary

10print(some_dictionary) # Results in {'Billy': 74, 'Sally': 88, 'Jimmy-Bob': 99}

In the example, a dictionary was created and three values were added to the dictionary

But values are associated with unique keys

The keys must be unique, but the values do not need to be

The keys in the example are

"Billy","Sally", and"Jimmy-Bob"Each of the keys have an associated value —

74,88, and99respectivelyAccessing a value from a specific key from the dictionary is done with indexing

1print(some_dictionary["Jimmy-Bob"]) # Results in 99

2print(some_dictionary["Sally"]) # Results in 88

And updating a value associated with a key is done just like the original assignment

Keys are unique, so using an existing key would overwrite the value and not make a new entry

1some_dictionary["Sally"] = 90

2print(some_dictionary["Sally"]) # Results in 90

15.2.1. Why They Are Great

Instead of using a dictionary to store the grades, imagine using a 2D list

1my_grades = []

2my_grades.append(["Billy", 74])

3my_grades.append(["Sally", 88])

4my_grades.append(["Jimmy-Bob", 99])

5print(my_grades) # Results in [['Billy', 74], ['Sally', 88], ['Jimmy-Bob', 99]]

How would I obtain the grade for a specific student?

I would need to do a linear search for the student’s name before I could access the grade

Assuming I have some

linear_searchfunction

1the_student = linear_search(my_grades, "Sally") 2grade = the_student[1] 3print(grade) # Results in 88

Alternatively, with a dictionary, it’s much simpler — just index the dictionary on the student’s name

Assuming

my_gradeswas a dictionary likesome_dictionaryinstead of a list of lists

1grade = my_grades["Sally"] 2print(grade) # Results in 88

In addition to being simpler syntax, the dictionary eliminates the need for the linear search

Remember, the amount of work needed for a linear search grows as the number in the collection grows

If we don’t need to do the linear search, we eliminate all that extra work

Note

Remember how the sum function still requires the computer to look at each value in a list, but that

functionality was hidden from us. Dictionaries are not simply hiding the linear search from us; its actual

underlying functionality does not need to do a linear search (although, there are some exceptions to this).

We will not be going into more details on how dictionaries work in this course, but that does not stop us from using and taking advantage of the dictionary’s benefits.

15.3. Sets

Another common data structure is sets

You may already be familiar with the idea of sets from math

When comparing to lists, sets are a little different

Elements in the set are unique, but lists can have multiple copies of the same value

Sets have no intrinsic ordering, but lists do (starting at index

0)

Consider the below example of students in a course

1csci_161 = set({"Greg", "Anna", "Sally", "Frank", "Frank"})

2print(csci_161) # Results in {'Frank', 'Sally', 'Greg', 'Anna'}

Notice that, although

"Frank"was included twice, it only exists once in the setAlso notice that the order of the elements is not the order they appear when the set was created

Below is another example of a set, but this time an additional name was added to the set after creation

1math_106 = set({"Frank", "Ryan", "Sally", "Francis", "Xavier", "Linda"})

2math_106.add("Lynn")

3print(math_106) # Results in {'Ryan', 'Xavier', 'Frank', 'Sally', 'Francis', 'Lynn', 'Linda'}

One can check if a given thing exists within a set with the

inoperatorLike a dictionary, checking if something is

inthe set does not require a linear search

1print("Ryan" in csci_161) # Results in False

2print("Ryan" in math_106) # Results in True

There are many other things you could do with a set, such as

Iterating over the contents with a

forloopRemove elements from the set

Check is sets are equal

Check if something is a subset of another set

Turn the set into a list (and you can turn a list into a set)

…

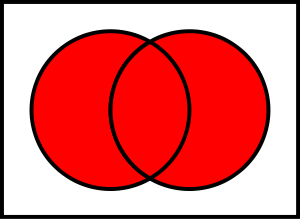

Three operations of note for sets are union, intersection, and difference

Union allows us to combine all elements from two sets into one set

For example, getting all the students from two courses

1all_students = csci_161.union(math_106)

2print(all_students) # Results in {'Ryan', 'Greg', 'Frank', 'Sally', 'Anna', 'Linda', 'Xavier', 'Francis', 'Lynn'}

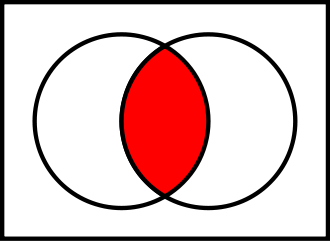

Intersection allows us to find elements that are common to both sets

For example, which students are in both CSCI 161 and MATH 106

1taking_both_courses = csci_161.intersection(math_106)

2print(taking_both_courses) # Results in {'Frank', 'Sally'}

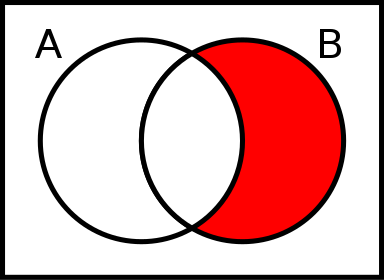

Set difference allows us to ask which elements are in one set but not in the other

For example, which students are taking CSCI 161 and not taking MATH 106

1only_taking_csci = csci_161.difference(math_106)

2print(only_taking_csci) # Results in {'Greg', 'Anna'}

Unlike union and intersection, the order of the operands for set difference matter

1only_taking_math = math_106.difference(csci_161)

2print(only_taking_math) # Results in {'Ryan', 'Linda', 'Xavier', 'Francis', 'Lynn'}

Activity

Imagine I gave you the text from a book that you could load up into Python. What’s the easiest way to count the number of unique words?

What would you do if I gave you another book and asked you which words do they have in common?

What if I wanted to know the number of unique words that exist between the two books?

What If I wanted to know which words were in one book, but not the other?