7. Testing Your Code and Type Hints

Writing code is a big part of your job when programming

But testing and debugging your code is a bigger part

7.1. Testing

Once you write a function, you need to ensure that it is actually correct

Once a function is written we often call it a few times to check that it is doing what we expect

But we want to be a little more systematic and thorough in our tests

We end up writing small snippets of code designed to test our code

In addition to ensure correctness, writing tests for our code also helps us think about our code more

What is correct/incorrect

Different cases that your function needs to deal with

If there are any edge cases

7.1.1. Writing Tests

For simplicity, we will keep our testing strategy to assertions about the data

Let’s say we want to test the absolute value function

absThis function is provided to you by Python, so there is no actual need to test it here

If we are to consider how we could test the

absfunction, we want to check that the function output (returns) matches what it should be based on the input (arguments)There is not too much to check with

absCheck that the absolute value of a positive number is itself

Check that the absolute value of a negative number is the positive version of itself

Check that the absolute value of zero is zero

Checking zero is perhaps not necessary, but it is somewhat of a peculiar case since zero doesn’t have a sign, so it is good to test it

1assert 5 == abs(5)

2assert 5 == abs(-5)

3assert 0 == abs(0)

If we run the above example, we should expect the program to produce no output since the assertions were all correct

For the sake of demonstrating what would happen if an assertion failed, here is a broken absolute value function

1# Broken

2def broken_abs(x):

3 return x

4

5assert 5 == broken_abs(5)

6assert 5 == broken_abs(-5) # Should Fail

7assert 0 == broken_abs(0)

The above

broken_absis clearly not correct as it just returns whateverxis, regardless of the signIf we run this code, we would see an error message like this

assert 5 == broken_abs(-5)

AssertionError

This is Python telling us that the assertion failed

More precisely, it failed on the input of

-5This now informs us that the function is not correct, and under which condition it is not correct

7.1.1.1. Square of Sums Example Tests

1def square_of_sum(a, b): 2 """ 3 Calculate the square of the sum of the two provided numbers. 4 E.g. 5 square_if_sum(2, 3) -> 25 6 7 :param a: First number 8 :param b: Second number 9 :return: The square of the sum of a and b 10 """ 11 c = a + b 12 d = c * c 13 return d 14 15 16# Tests for square_of_sum function 17assert 0 == square_of_sum(0, 0) 18assert 0 == square_of_sum(1, -1) 19assert 100 == square_of_sum(5, 5) 20assert 100 == square_of_sum(-5, -5) 21# To address precision issues, we can look for a sufficiently small difference between the expected and actual 22assert 0.001 > abs(square_of_sum(2.2, 2.2) - 19.36)

In the above example, the

square_of_sumfunction is tested a number of times under different input casesTake care to notice that the cases are not just testing different arbitrary input values, but the input values are trying to capture broader cases

What happens when the input is zero?

The input has a positive and negative?

There are two positives?

The input is all negative?

What happens when we have floating point numbers?

We look to capture the broad cases as it is not reasonable to test all possible inputs

Further, it’s not necessary to test all possible cases

If we test

square_of_sum(5, 5), it’s reasonable to assume thatsquare_of_sum(6, 6)would also be fine

Note

Notice how the last test looks a little different — assert 0.001 > abs(square_of_sum(2.2, 2.2) - 19.36).

This will be discussed in more detail a little later in the course, but briefly, computers are not great with floating point numbers.

What comes after the integer \(1\)? That’s easy, it’s \(2\).

What comes after the floating point number \(1.0\)? Is it \(1.1\)? Or \(1.01\)? Maybe \(1.00001\)?

If I run square_of_sum(2.2, 2.2), the correct answer is 19.36, but Python will say 19.360000000000003

due to the floating point number issue.

The simple way to address this issue is to check that the absolute difference between the expected answer and

the function’s result is less than some threshold. In the above example, the absolute difference between the

correct answer and what Python says is 0.000000000000003, which is a tiny difference; the numbers are nearly

identical. I chose a threshold of 0.001, so if the absolute difference between the expected and actual result is

less than that threshold, I will consider that a passed test.

The choice of the threshold will depend on the situation. Above I could have picked a much smaller number and the

test would have passed. But imagine you are a chemist using instruments that can measure to the nearest milliliter.

There would be no sense testing beyond a difference of 0.001 liters since you cannot get beyond that precision

in real life with those instruments.

Long story short, if you want to check equality between floating point numbers — don’t. Simply check that their difference is less than some reasonable threshold.

The above tests do a good job at catching the different scenarios

But you may be wondering why I didn’t test some other case like when the inputs are both positive, but different values

Something like

square_of_sum(5, 6)

Or why didn’t we test when the first argument was negative and the second was positive

square_of_sum(-1, 1)

Including these tests is not unreasonable, so maybe they should have been included

If you had included these cases in your tests, and perhaps some others, you would not be wrong

Testing can feel a lot more like an art than a science

7.1.1.2. Celsius to Fahrenheit Example Tests

1def celsius_to_fahrenheit(temp_in_celsius: float) -> float: 2 """ 3 Convert a temperature from Celsius units to Fahrenheit units. 4 5 :rtype: float 6 :param temp_in_celsius: The temperature in Celsius to be converted. 7 :return: The temperature in Fahrenheit. 8 """ 9 partial_conversion = temp_in_celsius * 9 / 5 10 temp_in_fahrenheit = partial_conversion + 32 11 return temp_in_fahrenheit 12 13 14# Tests for celsius_to_fahrenheit function 15assert 32 == celsius_to_fahrenheit(0) 16assert -40 == celsius_to_fahrenheit(-40) 17assert 23 == celsius_to_fahrenheit(-5) 18assert 86 == celsius_to_fahrenheit(30) 19# To address precision issues, we can look for a sufficiently small difference between the expected and actual 20assert 0.001 > abs(celsius_to_fahrenheit(32) - 89.6) 21assert 0.001 > abs(celsius_to_fahrenheit(37.7777) - 100)

Above is a series of assertion tests for the

celsius_to_fahrenheitfunctionNotice the key, broad tests

Input of zero

Input when Celsius and Fahrenheit are equal

Negative input

Positive input

Input is a float

Output is a float

If you were writing tests for this function and ended up having a few more tests that are arguably unnecessary, that’s OK

Note

It needs to be re-emphasized how important testing is. Writing code is only a small part of programming, and if your code isn’t even correct, then you haven’t solved the problem.

There is an argument for thinking about your tests before actually writing the function. This gets you to really think about the problem to better prepare yourself for writing the code.

Further, if you find you have a function that is particularly difficult to write tests for, perhaps the function you wrote is also too difficult to use? By thinking about testing first, you can hedge against this problem.

7.1.2. Automated Testing

Many programming languages have systems for automating tests with extra helpful functionality

In Python, there are two very popular modules to facilitate this

unittest— The standard Python testing frameworkpytest— Another popular framework

These require quite a bit of programming knowledge to use effectively, so we will not cover them here

But

unittestwill be discussed later in the course once the requisite knowledge has been covered

Regardless, at this stage these frameworks are overkill and the assertions we are using are more than sufficient

7.2. Type Hints

Python does a pretty good job at figuring out the types of data for us

However, it can only do so much, and at the end of the day it’s going to follow the code that you write

Unfortunately, when types get mixed up, we can end up with some serious bugs in our code

Try running the following code and see if it acts the way you expect

1def add_together(a, b): 2 """ 3 Calculate and return the sum of the two provided numbers. 4 5 :param a: First number 6 :param b: Second number 7 :return: The sum of the two numbers 8 """ 9 return a + b 10 11x = input("First number: ") 12y = input("Second number: ") 13result = add_together(x, y) 14print(result)

The trouble here is, chances are, one would expect the function to work on numbers

But when we read the input, we didn’t change the strings to numbers

So, although we intended for the function to add two numbers together, Python assumed you knew what you were doing when you provided strings as arguments to the function

7.2.1. Setting Type Hints

We can tell Python what the types should be when writing the functions

We can also tell Python what the return type should be too

We do this with type hints

Below is the

add_togetherfunction with type hints included

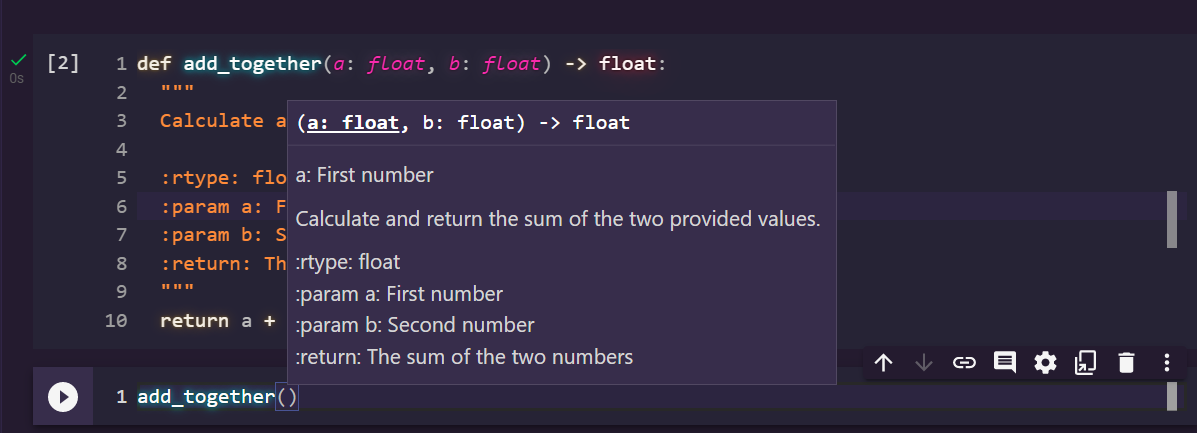

1def add_together(a: float, b: float) -> float: 2 """ 3 Calculate and return the sum of the two provided values. 4 5 :rtype: float 6 :param a: First number 7 :param b: Second number 8 :return: The sum of the two numbers 9 """ 10 return a + b

In the parameter list, each parameter’s type is explicitly stated

The return type of the function is also stated after the parameter list

This part

-> float:

It is also good to include the return type in the docstring for the function

:rtype: float

7.2.2. What You Get

Now, whenever some reads the description of the function they will know what the types are intended to be

In Colab, you will also see a popup when trying to call the function with the details of the function. including the types

7.2.3. What You Don’t Get

Unfortunately, Python will not actually stop you from using the wrong types

They’re more for documentation and other programmers

In other words, the inclusion of type hints would not actually address the original problem

1def add_together(a: float, b: float) -> float: 2 """ 3 Calculate and return the sum of the two provided values. 4 5 :rtype: float 6 :param a: First number 7 :param b: Second number 8 :return: The sum of the two numbers 9 """ 10 return a + b 11 12x = input("First number: ") 13y = input("Second number: ") 14result = add_together(x, y) 15print(result)

In the above example, despite type hints being included, it would behave the same way as it did without type hints.

It would still concatenate the strings

7.3. For Next Class

If you have not yet, read Chapter 5 of the text