22. Recursion

How many people are in this line?

How does one count them?

Just by looking at the first person, it’s exactly

1 +the number of people after the first person

22.1. Iterative Definition vs. Recursive Definition

Iterative definitions of things are fairly natural

Recursion on the other hand may feel a little less natural, but it pops up a lot in everyday life and in nature

22.1.1. Groups of People

Like the line of people example above, it may seem like a silly question because it is so intuitive

A group of people is:

2 people

OR 3 people

OR 4 people

OR …

…

…

Alternatively, the idea of recursion can be used to define a group of people a different way

When defining something recursively, the definition of something is used within its definition

Define something in terms of itself

A recursive definition of a group of people is:

2 people

OR a group of people plus one more person

Based on this recursive definition, if asked if 2 people are a group of people, the answer is clearly yes

It’s the first part of the recursive definition of a group of people

But if asked if 4 people is a group of people, some more digging is needed

In order to know if 4 people is a group of people, it needs to be known if 3 people is a group of people

If 3 is, then it can be concluded that 4 is since 4 is 3, a group of people, plus one more person

This is the second part of the recursive definition of a group of people

To know if 3 people is a group of people, it needs to be known if 2 people is a group of people

If 2 is, then it can be concluded that 3 is since 3 is 2, a group of people, plus one more person

By definition, 2 people is, in fact, a group of people

Therefore, 3 people is a group of people

Thus, 4 people is a group of people

In the above recursive example, notice a base case and a recursive case

The base case is something with a clear definition

The recursive case is one that defines something in terms of itself

Warning

Although there is no hard rule saying that a base case is needed, and there are examples of situations where it

would not be included, not including a base case is a recipe for disaster. Remember the uhOh() example from the

Memory & The Call Stack topic?

For the purposes of this course, always include a base case.

22.1.2. Lists

Think of a list from Python, or a linear linked structure

One can define this recursively in a rather natural way

A list is:

Base Case — An empty list

Recursive Case — There is a head of the list, followed by a tail — the remaining portion of the list

Consider the following list

[a, b, c, d, e]This can be broken down into the head

aand the tail[b, c, d, e]a + [b, c, d, e]The tail list can be broken down again and again until the empty list (base case) is hit

a + b + [c, d, e]a + b + c + [d, e]a + b + c + d + [e]a + b + c + d + e + []

22.2. Repeating Patterns

In counting example, it may feel like cheating by saying “1 + however many are after the front”

“however many are after the front” seems like skipping a step

But, with the list example, it was observed that repeatedly applying the same rule over and over on smaller and smaller lists resulted in hitting an end

The empty list

The base case

This pattern arises a lot with recursion — repeatedly apply the same rules on slightly different versions of the problem

As mentioned earlier, there is typically going to be a base case and a recursive case

In fact, there can be multiple base cases and recursive cases

Several examples of this will be seen when discussing trees

22.2.1. Going Up and Down

The set of natural numbers \(\mathbb{N}\) can be recursively defined as:

0 is a natural number

A natural number \(+ 1\) is a natural number

This recursive definition provides a complete definition of \(\mathbb{N}\)

One can start at the base case and repeatedly apply the recursive case to generate all natural numbers

This is a great way to mathematically define something infinite

Though, computers will not be all too happy with running this

One could also take this definition and use it to answer questions by working down to the base case, and then back up with the answer

Is \(4\) a natural number?

Is \(3 + 1\) a natural number?

Is \((2 + 1) + 1\) a natural number?

Is \(((1 + 1) + 1) + 1)\) a natural number?

Is \(((((0 + 1) + 1) + 1) + 1)\) a natural number?

\(0\) is a natural number

Therefore \(1\), which is \(0 + 1\), is a natural number

Therefore \(2\), which is \(1 + 1\), is a natural number

Therefore \(3\), which is \(2 + 1\), is a natural number

Therefore \(4\), which is \(3 + 1\), is a natural number

22.3. Recursive Programming

The factorial, \(n!\), of a non-negative integer is the product of all non-negative integers between \(n\) and \(1\) inclusively

It also includes zero, but this is addressed below

\(n! = n \times (n - 1) \times (n - 2) \times \dots \times 3 \times 2 \times 1\)

This can nicely be defined recursively

Note

Notice that \(0! = 1\). This is because:

It is \(1\) by definition (because someone said so), but this isn’t really a satisfying answer

\(1\) is the multiplicative identity, and it is used as the result when multiplying no factors

This is just like how adding nothing together results in \(0\) — the additive identity

It also aligns with the gamma function

If asked what \(4!\) is, it can be calculated by applying the rules; there are no real tricks to it

\(4! = 4 \times 3!\)

\(3! = 3 \times 2!\)

\(2! = 2 \times 1!\)

\(1! = 1 \times 0!\)

\(0! = 1\)

\(1! = 1 \times 0! = 1 \times 1 = 1\)

\(2! = 2 \times 1! = 2 \times 1 = 2\)

\(3! = 3 \times 2! = 3 \times 2 = 6\)

\(4! = 4 \times 3! = 4 \times 6 = 24\)

1static int iterativeFactorial(int n) {

2 int factorial = 1;

3 for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++) {

4 factorial = factorial * i;

5 }

6 return factorial;

7}

1static int recursiveFactorial(int n) {

2 if (n == 0) {

3 return 1;

4 }

5 return n * recursiveFactorial(n - 1);

6}

Both the iterative and recursive functions do the same thing

But, doesn’t the recursive function have a sort of beauty to it?

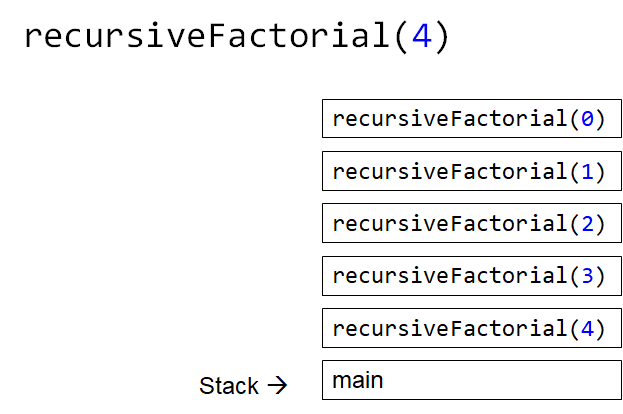

When considering the call stack, the stack will grow until it hits the base case

Then, each call frame will return the product to the calling function

Regardless of if the calling function is

recursiveFactorialormain

Example call stack of calling recursiveFactorial(4) when the program is currently executing the base case —

when n is 0. This is the state of the call stack before any values have been returned by any call frames.

22.4. Some Observations

Notice how

recursiveFactorial(4)makes a call torecursiveFactorial(3)If

recursiveFactorial(5)was called, it would need to calculaterecursiveFactorial(4)againIn other words, to know

recursiveFactorial(x), an answer torecursiveFactorial(x - 1),recursiveFactorial(x - 2), …recursiveFactorial(1), andrecursiveFactorial(0)must be calculatedOne many also notice the relationship between the

StackADT and the call stackAdditionally, anything that can be done with iteration can be done with recursion, and vice versa

However, just because it can doesn’t mean it should

Based on the design of the computational systems used, recursion creates additional overhead that slows things down

Creating call frames

Pushing/popping from the call stack

In some programming languages, like Java, compilers will optimize certain types of recursive functions by translating them to an iterative version

This does not mean, however, that one should not use recursion as sometimes recursive implementations are elegant and easier to write and understand

Simplicity of code may be tradeoff — remember, sometimes good enough is good enough

If performance needs improving later, do that later

Warning

The computers we as humans use are one type of computational system, and although recursion often ends up being slower than iteration on these computational systems, this is due to how the computational systems operate. Recursion is not intrinsically a slower process when compared to iteration.

22.5. Computational Complexity

When analysing code, it is important to think about many operations will be needed relative to an input size

nFurther, it is important to think about how much the amount of work done scales as

nchangesWhen looking at

iterativeFactorial(n)There are a few constant time operations (do not depend on

n)There is a loop doing constant time work that runs

ntimesTherefore, \(O(n)\)

When analyzing recursive functions, the idea is the same

How many operations will be needed relative to an input size

nHow much the amount of work done scales as

nchanges

When looking at

recursiveFactorial(n)There are constant time operations

There is a recursive call, which means the code inside this function can run repeatedly

The question then is, how many times will

recursiveFactorial(n)get called?

Accumulative times run |

Function call |

|---|---|

\(1\) |

|

\(2\) |

|

\(3\) |

|

\(\dots\) |

|

\(n - 1\) |

|

\(n\) |

|

\(n + 1\) |

|

With input

n,recursiveFactorialruns a total of \(n + 1\) times — \(O(n)\)It’s linear

22.5.1. Fibonacci

Consider the Fibonacci numbers

If not familiar with this sequence, try to figure out how it is created

\(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, ...\)

Here’s a hint

\(0, 1\)

\(0, 1, 1\)

\(0, 1, 1, 2\)

\(0, 1, 1, 2, 3\)

\(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5\)

\(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8\)

\(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13\)

\(\dots\)

To generate this sequence, start with \(0, 1\), then to get the subsequent number, add the proceeding two together

1static int iterativeFibonacci(int n) {

2 if (n == 0) {

3 return 0;

4 }

5 int previous = 0;

6 int current = 1;

7 int next = 0;

8 for (int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

9 next = current + previous;

10 previous = current;

11 current = next;

12 }

13 return current;

14}

What is the computational complexity of

iterativeFibonacci(n)?\(O(n)\)

The recursive definition of the Fibonacci numbers is quite elegant

1static int recursiveFibonacci(int n) {

2 if (n == 0 || n == 1) {

3 return n;

4 }

5 return recursiveFibonacci(n - 1) + recursiveFibonacci(n - 2);

6}

What is the computational complexity of

recursiveFibonacci(n)?This may feel a little less straight forward compared to

recursiveFactorial(n), but the idea is the sameThe function has constant time operations

But there are recursive calls, so, how many times does this function get called?

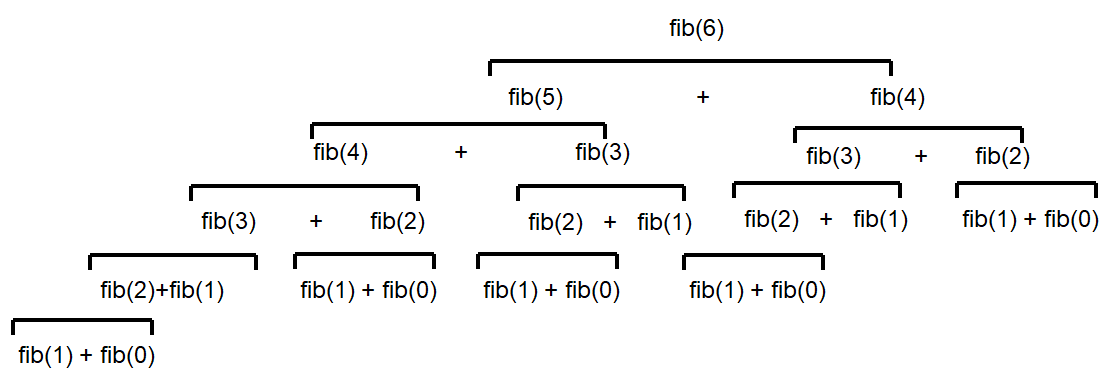

Visualization of the recursive function calls when calling recursiveFibonacci(6). Unless it is the base case,

each call to recursiveFibonacci produces two more recursive calls to recursiveFibonacci. Notice how many

times recursiveFibonacci(2) is calculated — 5.

When analyzing factorial (not Fibonacci), it was observed that each function call made one or zero recursive calls

There was

1recursive call for each of thenvalues between1–nThere was no recursive call in the base case

When looking at

recursiveFibonacci(n), how many potential recursive calls are there for each of thenvalues?Two

Each new call will call two more, which will call two more, which will call two more…

\(1\)

\(2\)

\(4\)

\(8\)

\(16\)

\(32\)

\(64\)

\(\dots\)

This patten follows \(2^{n}\)

Roughly speaking, the number of recursive function calls doubles each step

In other words, this recursive implementation is \(O(2^{n})\)

If given the choice between something that grows linearly or something that grows exponentially, take the linear

Despite the simple elegance of the recursive fibonacci implementation, this would be a good example of going back and improving the implementation for better performance

To get a sense of why the recursive version is so much worse than the iterative

Look at the above figure for a hint

When calculating

recursiveFibonacci(6),recursiveFibonacci(2)is calculated a total of \(5\) timesThe iterative implementation would have only calculated this once

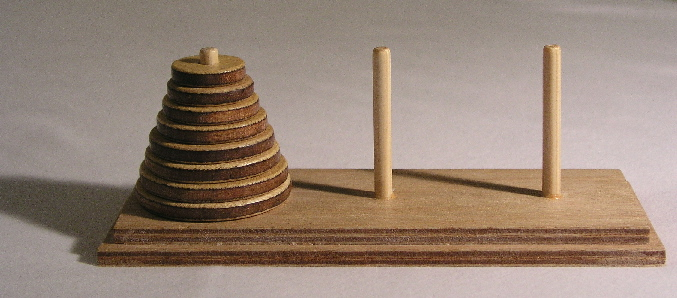

22.6. Towers of Hanoi

Given

Three pegs

Several disks that can be added or removed from the pegs

All disks vary in size

All disks start on one peg with the largest at the bottom and the smallest at the top

The goal is to move all disks from one peg to another with the following constraints

Only one disk can move at a time

A disk may never be placed on top of any smaller disk

All disks must be on some peg at all times, with the exception of the one currently being moved

Example Towers of Hanoi puzzle.

Animation of Towers of Hanoi being solved.

Towers of Hanoi is a classic example of where a recursive function is beautifully succinct

The trick is to consider that, whenever moving a disk, there is a source peg, a destination peg, and an extra peg

Further, what is considered the source, destination, and extra peg is relative to when and what disk is being moved

Equipped with this information, to move \(n\) disks from the source to the destination, simply

Move the \(n - 1\) disks from source peg to the extra peg

Move the \(n^{th}\) disk to the destination peg

Move the \(n - 1\) disks from the extra peg to the destination peg

Steps 1 and 3 may feel like cheating, but notice that they are actually recursive calls

Also, what one considers the source, destination, and extra peg will change when moving the \(n - 1\) disks

Looking at the first step, it says move the \(n - 1\) disks from source peg to the extra peg

Ok, how is that done?

Move the \((n - 1) - 1\) disks from source peg to the extra peg

Move the \((n - 1)^{th}\) disk from the source to the destination

Move the \((n - 1) - 1\) disks from extra peg to the destination peg

But, the extra and destination pegs are different for the \((n - 1)\) disks

The extra peg when moving \(n\) disks has become the destination peg when moving \((n - 1)\)

Similarly, the destination peg when moving \(n\) disks is this recursive step’s extra peg

Warning

This is a non-trivial problem and algorithm. If the ideas are difficult to grasp, don’t worry too much.

22.7. For Next Time

Read Chapter 8

28 pages