10. Genetic Operators

Below is a collection of common genetic operators for broad types of representations

This is by no means exhaustive

Further, it should not be assumed that they are particularly effective

They are intended to provide foundational ideas

These operators focus on representations for genetic algorithms

The motivation for focusing on genetic algorithms is they are quite a general form of evolutionary computation

Although common genetic operators are presented, being creative and trying to invent new operators is encouraged

10.1. Genetic Operators for Binary Representations

Binary representations are those that only contain two values, which are typically 0s and 1s

10.1.1. Crossovers

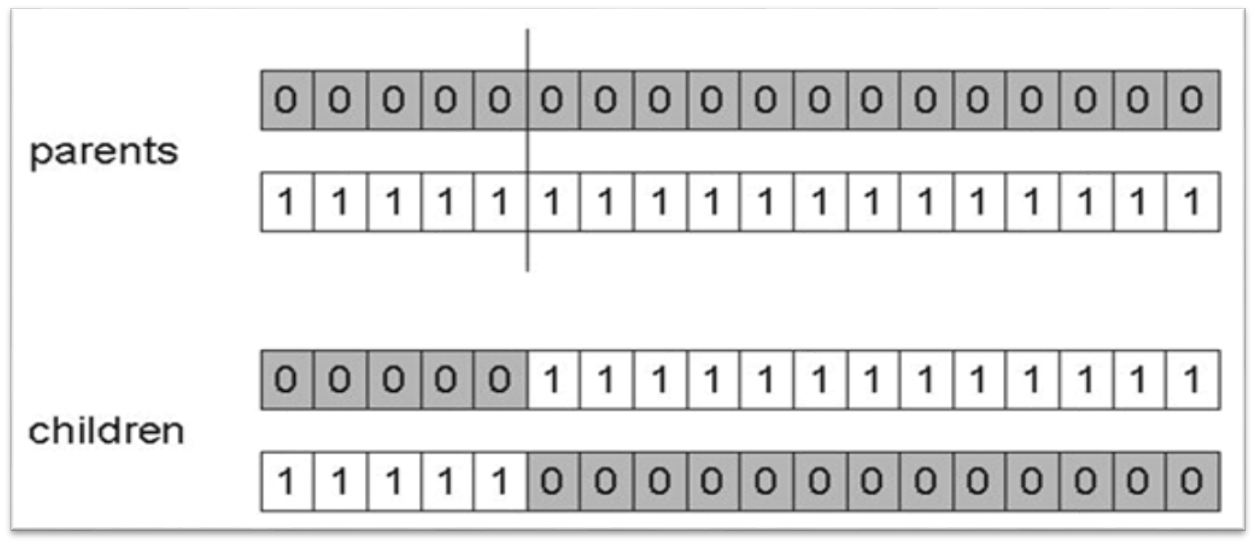

10.1.1.1. One Point Crossover

Randomly select an index

Exchange the elements between the chromosomes after that index

This crossover is not particularly destructive

The amount in which the information within the chromosomes gets changed is low

This crossover works well when element adjacency in the chromosome is important

Result of applying one point crossover on two chromosomes. This example has index 5 as the randomly selected crossover point, thus, all elements after index 5 are exchanged between the parent chromosomes. Although this example shows one parent containing only 0s and the other containing only 1s, this is not a requirement; the parents could contain both 0s and 1s.

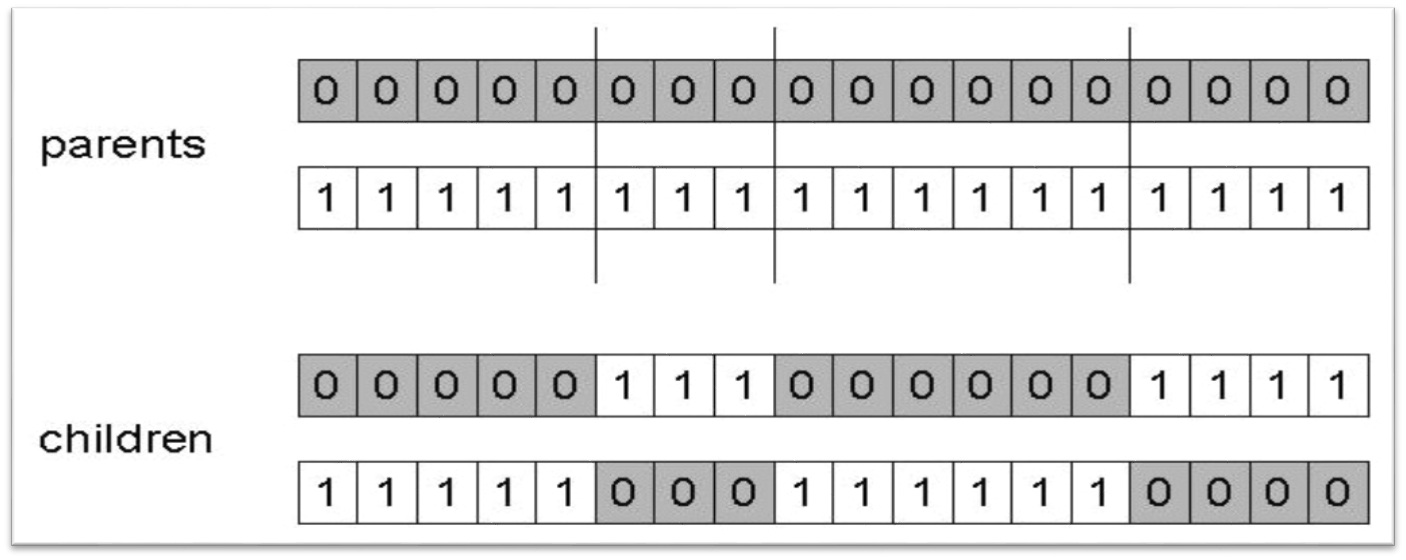

10.1.1.2. \(n\) Point Crossover

Randomly select \(n\) indices

Exchange the elements between every other pair of indices the indices

If an odd number of indices, exchange the elements from the last index to the end

This is a generalization of one point crossover

\(n=2\) is popular (two point crossover)

Result of applying \(n\) point crossover where \(n=3\). The randomly selected indices in this example are 5, 8, and 14. All elements between indices 5 and 8 (exclusively) are exchanged along with all the elements from index 14 to the end of the chromosome.

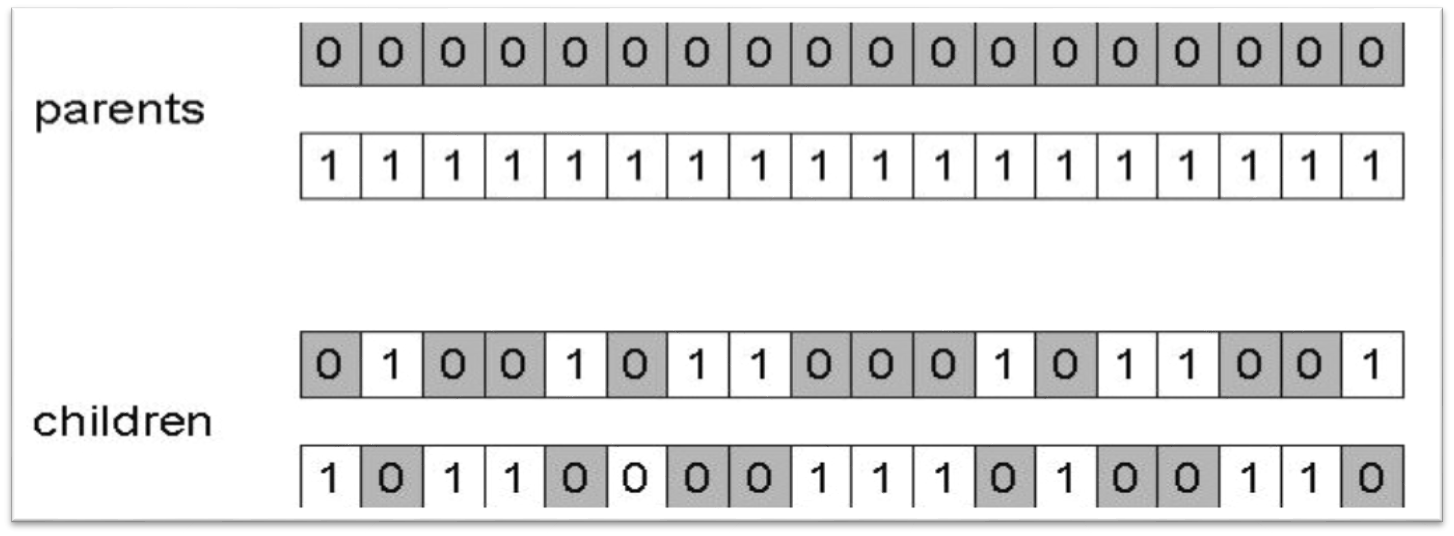

10.1.1.3. Uniform Crossover

Select some random number of indices at random

Exchange the elements at those indices

Often implemented by giving each index a 50/50 chance to be selected for crossover

This crossover is relatively destructive

Not particularly effective on chromosomes where element adjacency is important

Result of applying uniform crossover where the a total of 8 values were exchanged.

10.1.2. Mutations

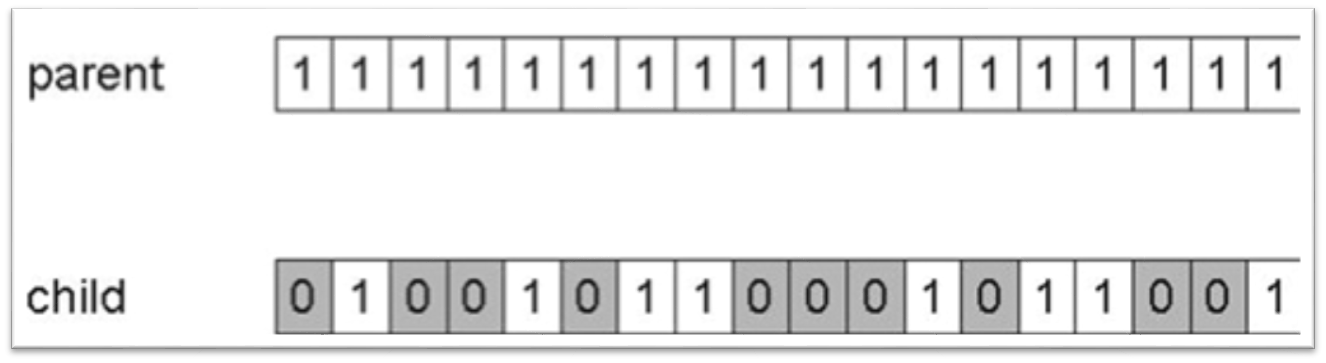

10.1.2.1. Bit Flip Mutation

Select some number of bits and flip them

Change 0s to 1s and 1s to 0s

The number of bits that get flipped is arbitrary

Could be hard coded

Could be randomly selected each time

Similar to uniform crossover, but instead of exchanging elements between parents, just change the binary symbol

As the number of bits that are flipped increases, so does the level of destruction this mutation causes

Result of applying a bit flip mutation to some chromosome. Here, a total of 10 bits were flipped during the mutation, which is a rather high number of bits to flip. Although this example shows the parent chromosome containing only 1s, this is not a requirement; it could have contained 0s that got changed to 1s.

10.2. Genetic Operators for Integer Representations

Integer representations are those that consist of integer values

10.2.1. Crossover

The crossovers used for binary representations are typically also used for integer representations

10.2.2. Mutations

10.2.2.1. Single Point Mutation

Sometimes called “Random Resetting”

Similar to the bit flip mutation

Select an index at random

Replace the value at the selected index with some other valid integer

A single point mutation can be generalized to an \(n\) point mutation by selecting multiple indices to change

This mutation is helpful in situations where the values within the chromosome represent cardinal attributes

Where the order of the possible integer values do not necessary matter

For example, the amount of values within a set

This mutation is also helpful in situations where each possible integer is equally likely to be within the chromosome

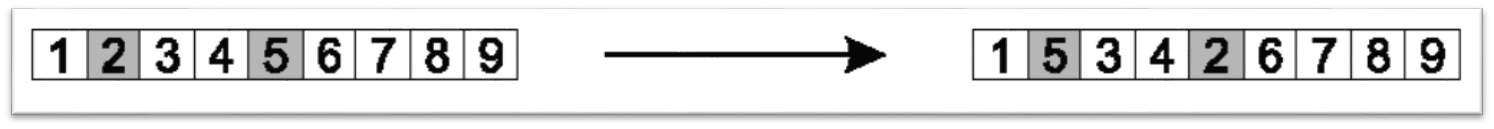

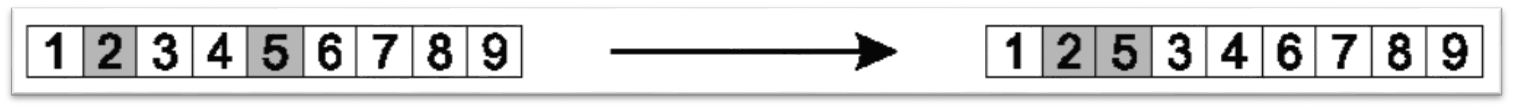

10.2.2.2. Swap Mutation

Select two indices at random

Swap the values at the selected indices

Can be generalized to a rotation mutation where many indices are selected and the values are rotated among them

This mutation preserves what information is within the chromosome

Now new information is added

Swap mutation applied to a chromosome where the selected indices are 1 and 4. The values at index 1 and 4 are swapped.

10.2.2.3. Creep Mutation

Select an index at random

Change the value at that index to one relatively close to the current value

For example, if the value at the selected index is 7, replace it with an 8

What close to means will depend on the context

This mutation is often used in situations where the values within the chromosome represent ordinal attributes

Where the order of the possible integer values matter

10.3. Genetic Operators for Permutation Representations

Permutation representations are those that consist of different orderings of values from some predefined set/multiset

For example

The representation used for the \(n\) queens problem was a permutation representation

Typically a permutation representation is used for TSP

Many of the previously discussed genetic operators are problematic since they may destroy the permutation property

10.3.1. Crossovers

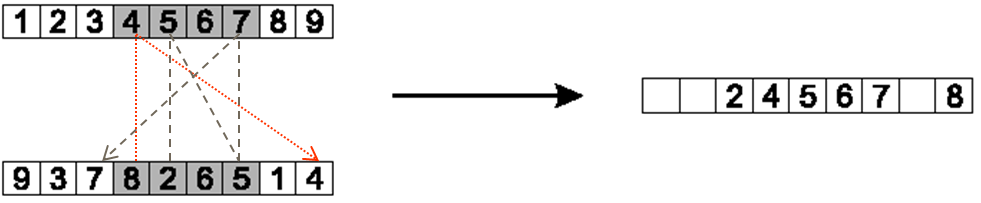

10.3.1.1. Order Crossover

Select two indices randomly

Copy the elements between the selected indices to a child

Copy the missing elements in the child from the other chromosome in the order they appear after the second index

Best described with an example

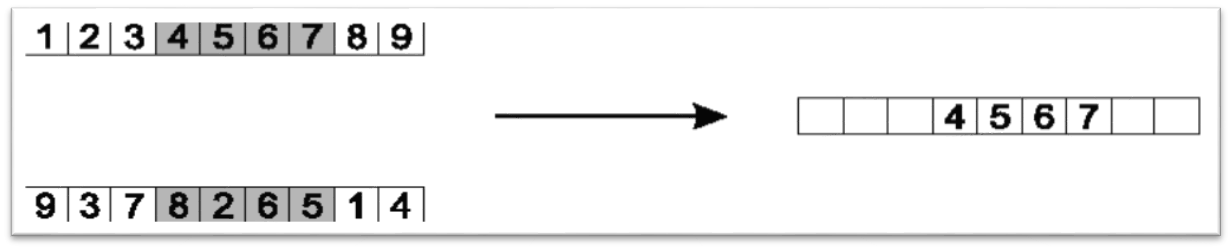

Select two indices at random

Here, indices 3 and 7 are selected

Copy the elements between the selected indices to a child chromosome

Typically the larger index is not included in the copy

Here, elements at indices 3, 4, 5, and 6 are copied

Copy the elements between the selected indices to a child. Only one child chromosome is shown here.

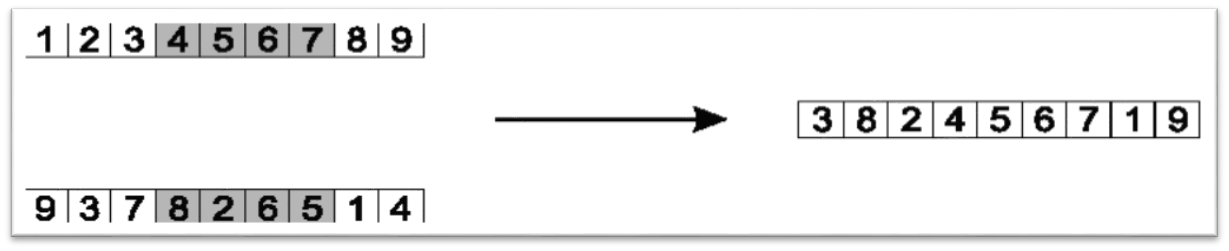

Copy missing elements from the other parent to the child in the order they appear, starting at the larger index

Wrap to index 0 where necessary

Here, the copying would start at index 7, which contains the element 1

The 1 would be copied to the child as it is not contained within the child chromosome

The value at index 8 is a 4, but would not get copied since it already exists in the child

The next index would be 0 as there is no index 9, which contains a 9, thus it is copied to the child

etc.

The values that are copied are 1, 9, 3, 8, and 2, in that order

Copy the elements from the other parent, in order, starting after the larger index. Only copy values that are not already contained within the child.

Repeat the same idea for the other child

10.3.1.2. Partially Mapped Crossover

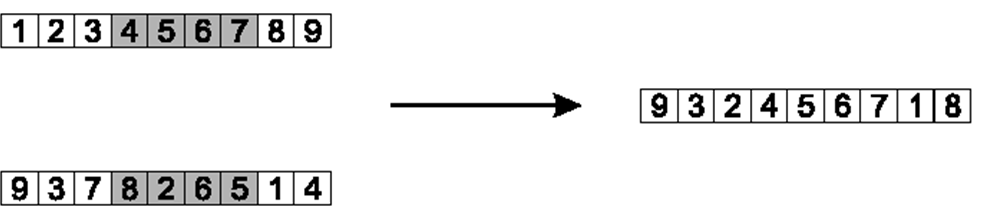

This one is rather complex and is tough to explain in words

Below are figures that help explain the process

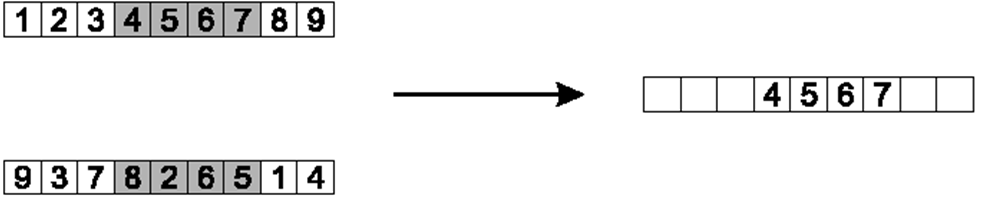

Select two indices at random

Here, indices 3 and 7 are selected

Copy the elements between the selected indices to a child chromosome

Typically the larger index is not included in the copy

Here, elements at indices 3, 4, 5, and 6 are copied

Copy the elements between the selected indices to a child. Only one child chromosome is shown here.

Starting at the first selected index and value in the other parent, copy non-copied elements to the child by

Find the index of the element that exists in the child in the non-copied parent

Here, the value of 8 is at index 3 in the non-copied parent and is also not in the child

The value in index 3 of the child is 4

The value of 4 exists at index 8 in the non-copied parent

Thus, the value of 8 is placed into index 8

It is possible that the index the value should be copied to is already filled

See the value 2 in the below figure

The value 2 would be copied to index 6, but index 6 is already occupied in the child chromosome

When this happens, the process is continued by looking back to what value exists at that index in the child

Example of how the values of 8 and 2 would be copied to the child.

Copy the remaining elements to the child in place

The elements that do not exist in the child are copied from the parent in place.

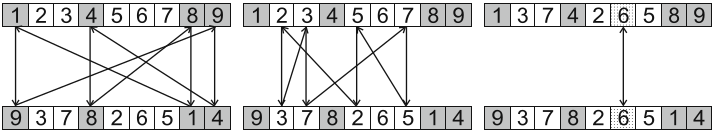

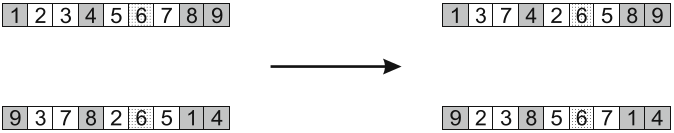

10.3.1.3. Cycle Crossover

Select an index at random

Identify the value at that index in parent 1

Get the value at the selected index in parent 2

Find the index of that value in parent 1

Repeat until a whole cycle is found

When the value at the original index in parent 1 is found in parent 2

Exchange the elements at the indices in the cycle between the parents

Three different cycles in the same two parents. One is shown in dark grey, one in white, and one in light grey. If the light grey cycle was selected (the one only containing 6s), no change would happen as a result of this crossover.

Result of applying cycle crossover. This is the result of using either the dark grey or white cycles identified above.

10.3.2. Mutations

The swap mutation discussed above is simple and works well

Same with the generalized rotation mutation

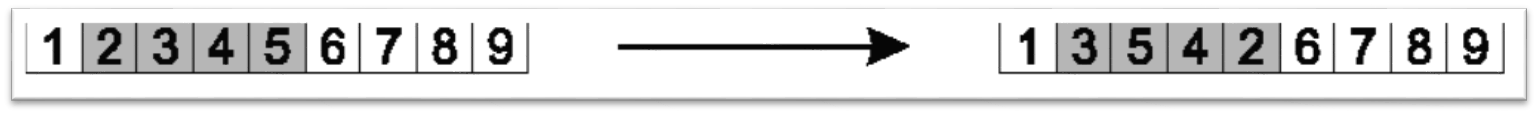

10.3.2.1. Insertion Mutation

Select two indices at random

Insert/move the value at one index before/after the value at the other index

Result of applying insertion mutation on a chromosome where indices 1 and 4 are selected. The value at index 4 was inserted after the value at index 1.

10.3.2.2. Scramble Mutation

Select two indices at random

Scramble/shuffle the vales between the selected indices

This mutation can be quite destructive

Scramble mutation being applied between indices 1 and 5 (exclusive). The resulting order of the shown scramble is arbitrary.

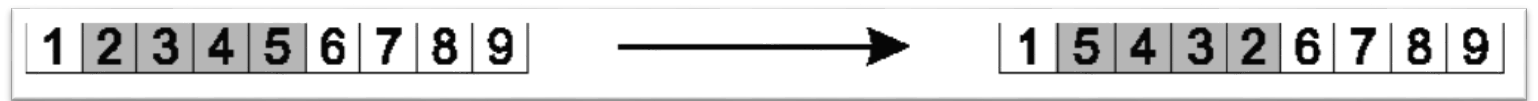

10.3.2.3. Inversion Mutation

Select two indices at random

Reverse the order of the elements between the selected indices

Not particularly destructive when the adjacency of elements in the chromosome is important

Inversion mutation applied to a chromosome where the selected indices are 1 and 5 (exclusive).

10.4. Genetic Operators for Floating Point/Real Number Representations

Floating point/real number representations are those that consist of continuous values

They are bound by the computer’s ability to represent real numbers as floating point numbers

There are many complex genetic operators for floating point/real number representations

Only a few of the relatively simple popular ones are discussed here

In practice, there are other forms of evolutionary computation that perform better with these representations

10.4.1. Crossovers

Two broad ideas

Discrete — offspring have values from parents

These would be those that were discussed for the binary representation

Intermediate — offing have values between the two parents

Select intermediate crossovers are discussed below

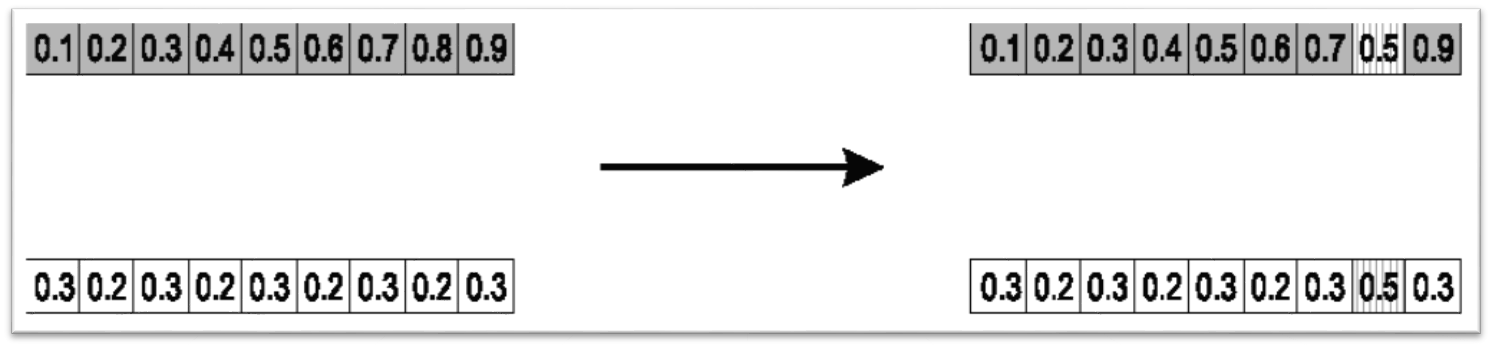

10.4.1.1. Single Arithmetic Crossover

Randomly select an index

Average the values between the parents at that index

Result of single arithmetic crossover where the selected index was 7. The values of 0.8 and 0.2 in the two parents are replaced with 0.5, the average of the values.

10.4.1.2. Simple Arithmetic Crossover

Similar to single point crossover

Randomly select an index

Average the values between the parents after that index

This crossover can be generalized to an \(n\) point version

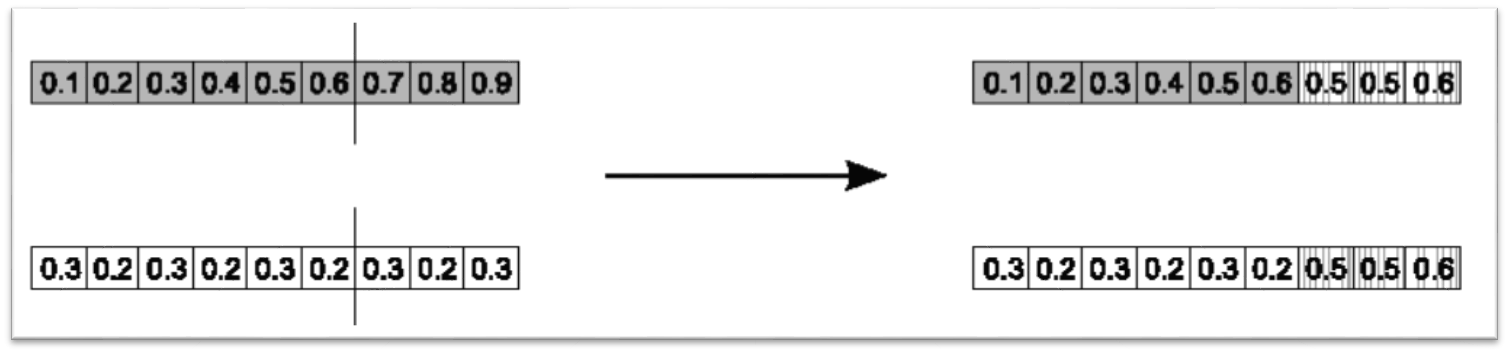

Result of simple arithmetic crossover where the selected index was 6. All values are averaged between the parents from index 6 to the end.

10.4.1.3. Whole Arithmetic Crossover

Average the values between the parents across all indices

This would be a special case of simple arithmetic crossover where the selected index was 0

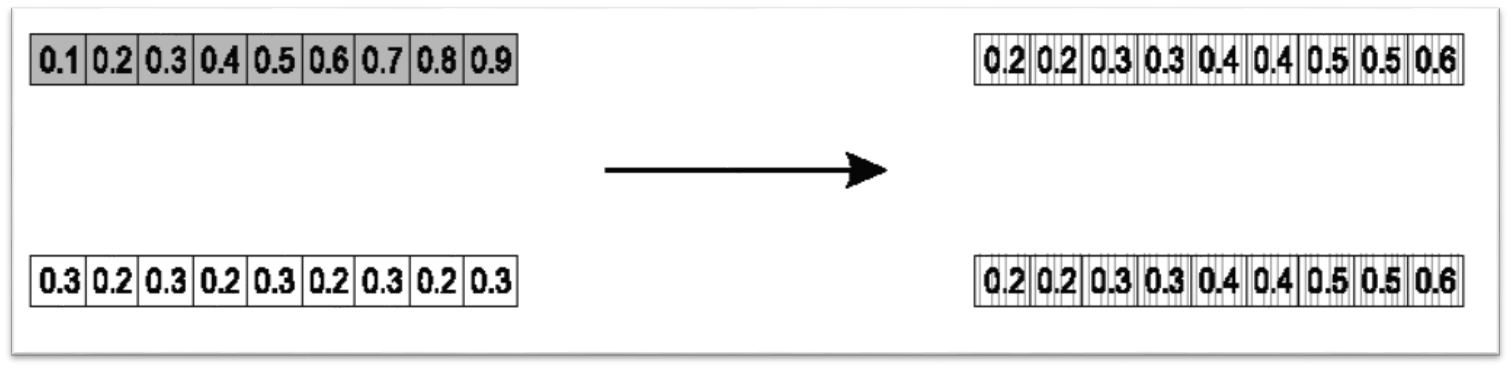

Result of whole arithmetic crossover. All values are averaged between the parents.

10.4.2. Mutations

10.4.2.1. Uniform Mutation

Randomly select an index

Replace the value at the selected index by a value from a continuous uniform distribution within some range

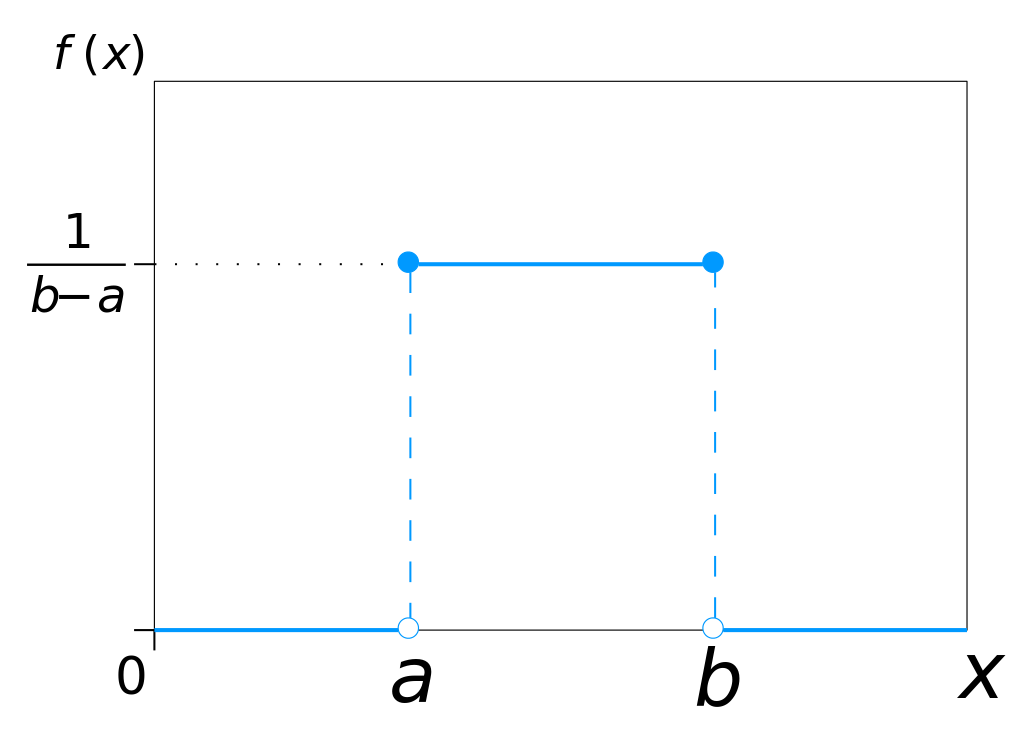

A continuous uniform distribution of values between \(a\) and \(b\).

10.4.2.2. Gaussian Mutation

Sometimes called non uniform mutation

Randomly select an index

Replace the value at the selected index by a value from a continuous normal/Gaussian distribution

The mean of the distribution is the original value at the selected index

This mutation is more likely to make small incremental changes

This mutation is particularly popular

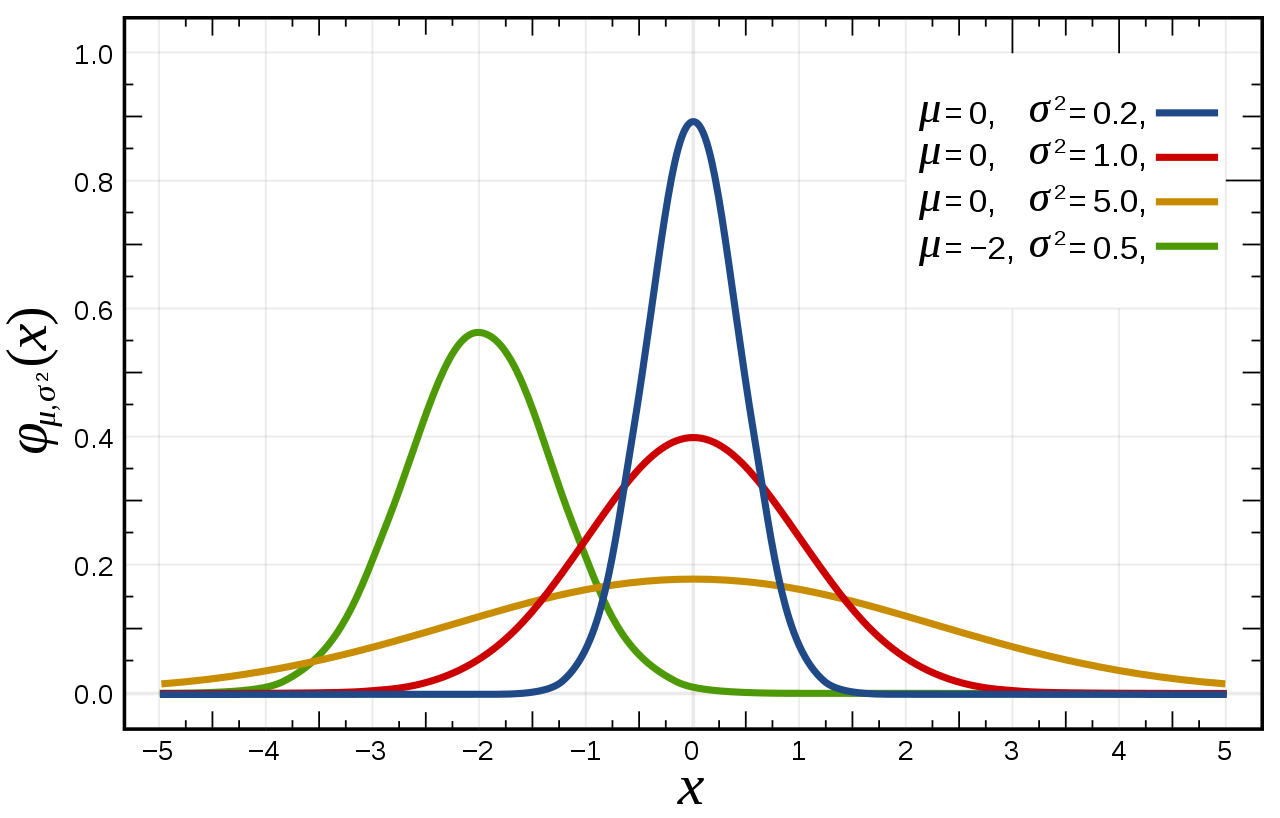

Three continuous normal/Gaussian distribution of values with different mean and variance values. The red curve is a “standard” normal distribution — has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

10.4.2.3. Self Adapted Mutation

A non uniform mutation, but the value of the variance of the normal/Gaussian distribution is part of the chromosome

The value of the variance is also evolved

This means the evolutionary search is also modifying the value of one of it’s parameters

10.5. Genetic Operators for Tree Representations

Tree representations are typically for genetic programming

However, genetic programming is really just a genetic algorithm where

The representation is a tree

The goal is to evolve some function/program

The generic operators can become tricky when working with typed genetic programming

This is discussed in a future topic

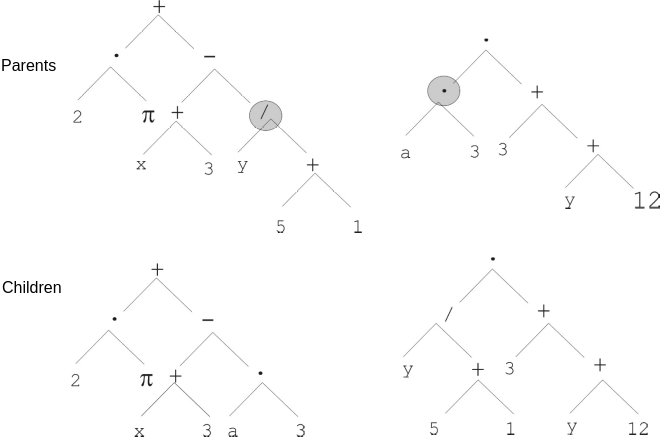

10.5.1. Crossover

Randomly select a node within each tree

Swap the subtrees between the parents

Swapping the subtrees rooted at the divide (\(/\)) and multiplication (\(\cdot\)).

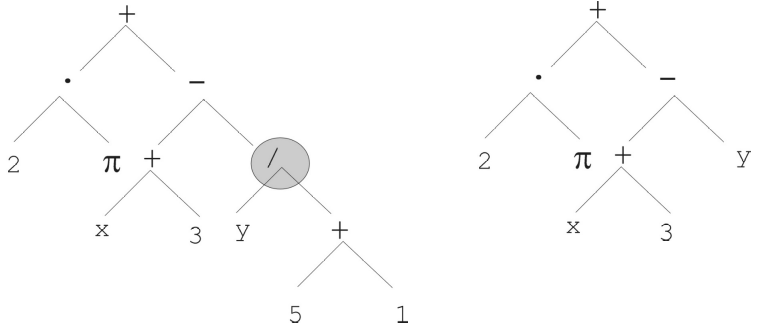

10.5.2. Mutation

Randomly select a node within the tree

Replace the subtree at that node with a newly generated subtree

Typically the newly generated subtree will be of some bound depth

The subtree with the root of divide (\(/\)) is replaced by the subtree of only the variable \(y\). Although the subtree is replaced with a new tree with only a root node, this is not a requirement.

10.6. Additional Notes

As stated above, this list is in no way exhaustive

It simply contains some common examples of genetic operators for various representations

The above are shown to give an idea of what is out there and what works

However, throughout this course, being creative and inventive with genetic operators is strongly encouraged

10.6.1. Destructive Operators

The word destructive was used above when referring to genetic operators

This term is not particularly well defined

Used to communicate how much the chromosomes change and/or how much the information within the chromosomes change

How destructive something is will depend on the representation and the problem

For example, a single point crossover on an integer representation for a robot navigating a maze

On average it changes half the chromosome, but the information in the chromosomes is preserved and transferred

The part of the chromosome that is transferred represents a sub-path that will move to the other chromosome

This is not particularly destructive

On the other hand, a uniform crossover on the same problem can be quite destructive

Since the integer adjacent is important for paths, changing out multiple single directions can have a large impact

10.6.2. Exploration vs. Exploitation

Consider the following population for a genetic algorithm maximizing the integer value with a single point crossover

This example was already discussed in an earlier topic

[[1, 0, 1, 1, 1], [1, 0, 0, 0, 1], [0, 0, 1, 1, 1], [1, 0, 1, 1, 1], [0, 0, 0, 1, 0]]

Notice how there exists no

1in any of the chromosomes’ index 1No matter how much the search exploits the information in the population, it cannot possibly add a

1to index 1Exploit in this context means making use of what is already known to be good

Because of this, it is not possible to find the optimal solution with single point crossover alone

This is where the bit flip mutation came in

It added new information to the population; it explored the search space

In this context, the bit flip was relatively destructive compared to the one point crossover

Thus, sometimes a destructive operator is very beneficial

It can improve the search’s ability to explore other areas of the search space

Further, consider a population that has converged on some local optimum

No matter how much the information in the local optimum is exploited, the search will likely remain stuck

By increasing the exploration, perhaps the search can work itself out of the local optimum

Note

These ideas are just high-level guidelines. Crossover is not always exploitative, nor is mutation always explorative. A destructive genetic operator is not always explorative nor is a less destructive one more exploitative.

These all depend on the context of the problem, representation, and how the operators are being used. In other words, use these ideas as a starting point for high-level decision making.

10.7. For Next Class

TBD