12. Genetic Programming

Genetic programming is using a genetic algorithm for evolving programs/functions

The genotype is typically a tree structure representing the program/function phenotype

Genetic operators that work on the tree encoding are used

Ultimately, it’s a genetic algorithm that searches the space of programs/functions

12.1. Example Problem — Breast Cancer Identification

Consider the problem of determining if an individual has breast cancer [1]

ID |

Thickness |

Size |

Shape |

Bare Nuclei |

Mitosis |

Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1000025 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Benign |

1002945 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

1 |

Benign |

1017122 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

1 |

Malignant |

1018099 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

1 |

Benign |

1041801 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

Malignant |

1043999 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

Benign |

1044572 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

9 |

4 |

Malignant |

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

The goal is to build a classifier to determine if a patient has breast cancer based on the observations

What should the classifier be?

If size > 4 and (shape == 3 or shape == 5) then malignant else benign?If thickness > 4 and thickness < 9 then malignant else benign?If mitosis == 1 then malignant else benign?

It would take careful study and a deep understanding of the problem to build a classifier manually

However, AI and Machine Learning are often used to automate the process of building a classifier

The AI and Machine Learning would try to generalize trends that exists in the observations within the data

Unfortunately, most evolutionary computation algorithms are not particularly designed to find models like this

Often they are used for combinatorial or real number optimization

This is where genetic programming comes in

With the use of a clever representation, genetic programming optimizes programs/functions

12.2. Representation

S-expressions (symbolic expressions) are commonly used as the representation for genetic programming

S-expressions are used to represent nested instructions and data

These s-expressions are commonly visualized as tree structures

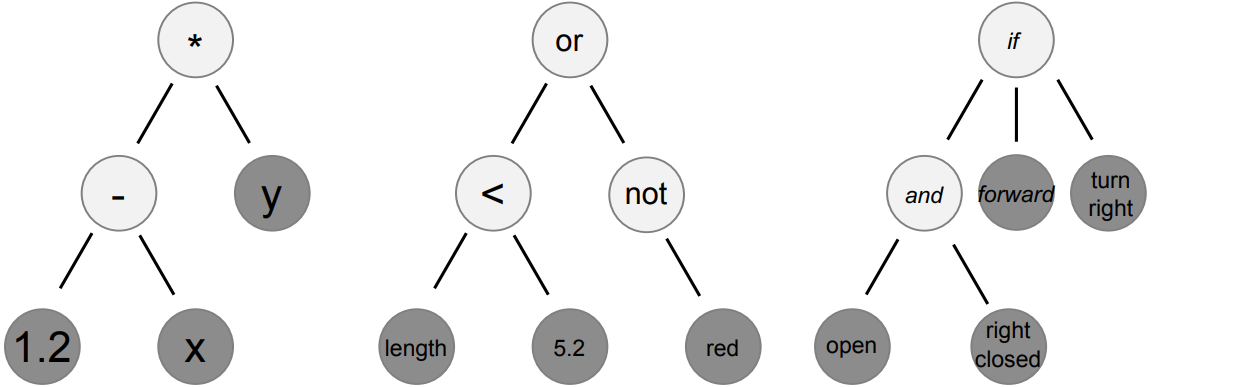

Three s-expressions shown as trees representing three different programs/functions. The left tree represents

the s-expression ((1.2 - x) * y), the centre tree represents ((length < 5.2) or not(red)), and the

right tree represents if((open and right_closed)) then(forward) else(turn_right). The light coloured nodes

represent operators while the darker nodes represent operands, both constants and variables.

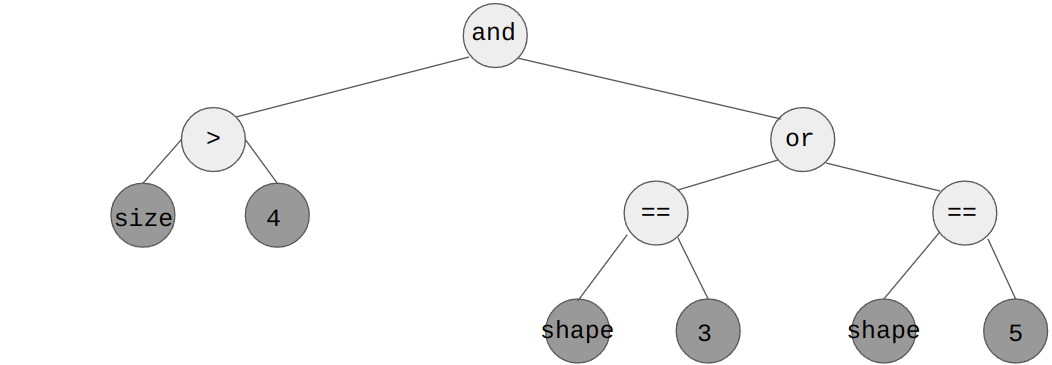

Consider the above program/function for the breast cancer identification problem

If size > 4 and (shape == 3 or shape == 5) then malignant else benign?

If

TRUEmeans malignant andFALSEbenign, the program/function can be written as the following s-expression((size > 4) and ((shape == 3) or (shape == 5)))

This s-expression can also be represented as the following tree

The program/function If size > 4 and (shape == 3 or shape == 5) then malignant else benign represented as a tree

structure.

12.2.1. Language

The set of available operators and operands use for creating and modifying the trees is called the language

The operators and operands are something that can be adjusted as needed

With the breast cancer example, the language could be a collection of arithmatic and boolean operators and operands

Operators

Binary Operators

\(+\)

\(-\)

\(\times\)

\(/\)

\(<\)

\(>\)

\(==\)

and

or

Unary Operators

\(sin\)

\(cos\)

\(e\)

not

Operands

Constants (e.g. \(4\), True, False)

Variables (e.g. size and shape)

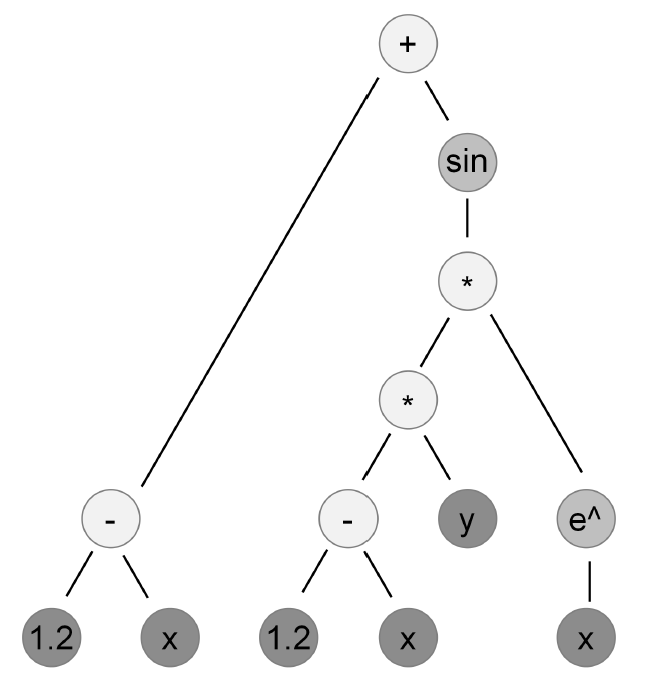

S-expression for the mathematical expression \((1.2 - x) + sin((1.2 - x) \times y \times e^{x})\). This tree contains arithmatic operators and operands (constants and variables).

When working with mathematical expressions, the language could be a collection of arithmatic operators and operands

Like the numerical operators and operands discussed above

12.2.2. Typed vs. Untyped

Notice that the mathematical expression example above only worked with numerical values

All the operators acted on numbers

All the operands, either constant or variable, would be numbers

However, the breast cancer example had multiple different types available

Some operators act on numbers to produce a number (e.g. \(+\))

Some operators act on numbers to produce a boolean (e.g. \(<\))

Some operators act on booleans to produce a boolean (e.g. and)

The operands may be either numbers or booleans

When using a language with only one type, like the mathematical expression, it is called untyped genetic programming

When using a language that has more than one type, it is called typed genetic programming

There is added complexity when working with typed genetic programming since the s-expressions must be admissible

Generating an s-expression that applies an operator to the wrong type would be a problem

For example,

(shape == 4) + 7is an inadmissible statement

With untyped genetic programming, this will not be a problem

Fortunately, most modern genetic programming systems will manage this complexity

12.3. Typical Genetic Programming Setup

A genetic programming algorithm is setup very similar to an ordinary genetic algorithm

Initialize a population

Evaluation

Selection

Genetic Operators

Termination

The key differences are around the tree representation

For example, the genetic operators must work with the trees

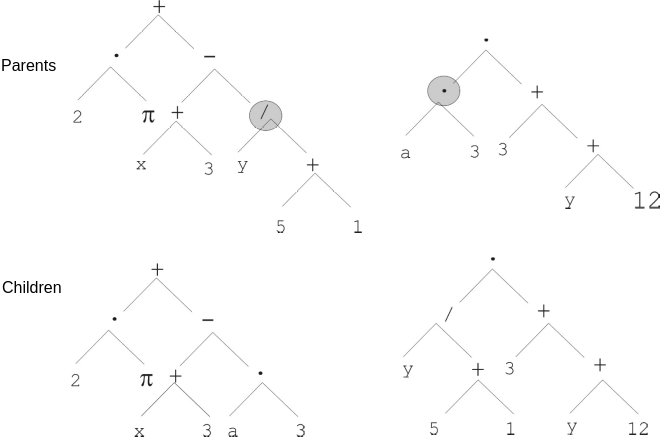

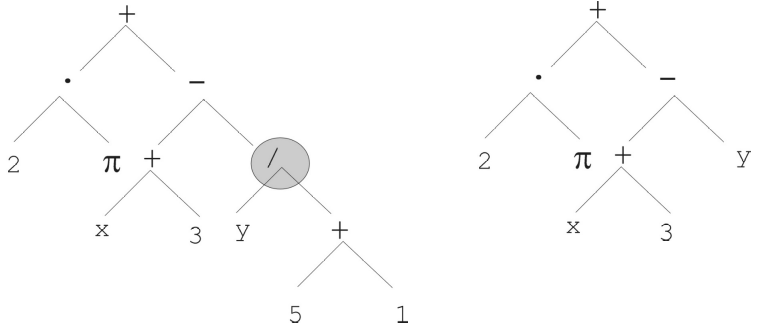

One point crossover on a tree structure. The two randomly selected subtrees are exchanged.

One point mutation on a tree structure. A randomly selected node in the tree is replaced with a randomly generated subtree. In this example, the subtree was replaced with a variable, but it could be been a more complex subtree.

Typically, for genetic programming, mutation rates are kept very low (less than 5%)

But ultimately, the value to use is a value that works well

Populations are also typically very large

12.4. Bloat

With genetic programming, during evolution, the average number of nodes in the trees increase quickly

And it is common that this happens with no significant improvement in fitness

This is problematic since

The trees take up more space

They take longer to evaluate

They tend to overfit and generalize poorly

The trees are difficult to interpret

The variation operators become less effective

There are three explanations for this phenomenon

Replication accuracy theory

Parents are selected for having a good fitness

Children with a function similar to their parents will also be relatively good

Larger trees are functionally impacted less by genetic operators

Thus, large and bloated trees are more likely to be similar to their parents

Removal bias theory

Useless subtrees with no meaningful function may exist within the tree

With larger trees, there is a higher chance to have useless subtrees

Applying genetic operators to useless subtrees has no impact on the fitness of the chromosome

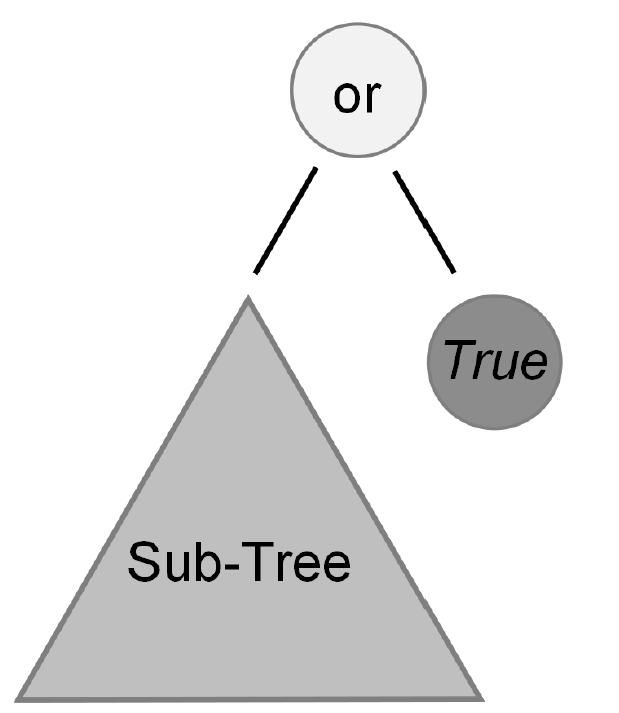

A tree that always evaluates to true, regardless of what is contained within the left subtree, which may be arbitrarily large.

Note

In evolutionary computation, “useless” information may not be useless over the course of evolution. This vestigial information within the chromosome may have been useful at some time, but became not represented in the phenotype.

It is also possible that this information reemerges as useful. For example, consider some subtree within the “useless” subtree in the above figure. Although it may not be expressed in the phenotype of this tree, it may end up expressed in some other tree’s phenotype via crossover.

Nature of program space theory

With a fixed language, there are more larger programs

The number of larger programs with a given function is greater than the number of short programs with the same function

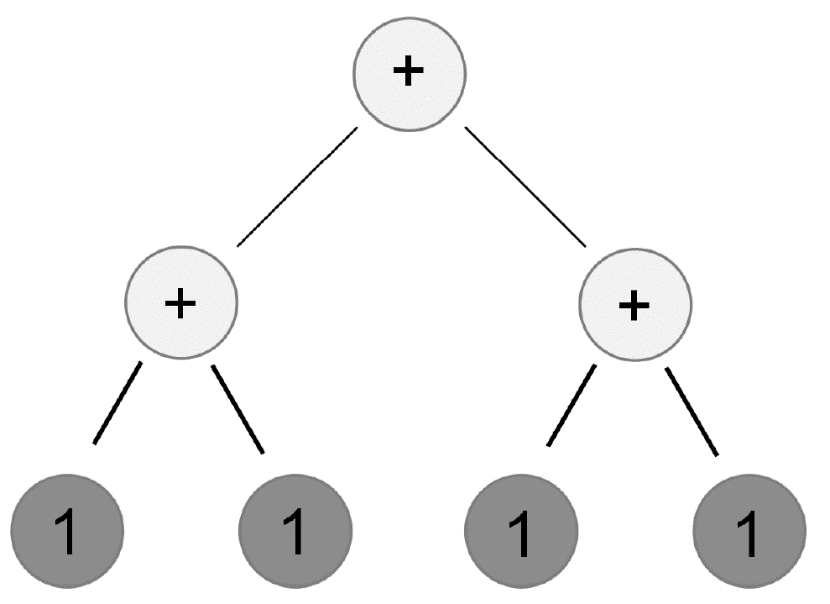

A tree with seven nodes that evaluates to 4. Consider the number of trees of size one that would also return 4 and then consider the number of trees of size three that would return 4.

Like everything, there is no right answer, but there are popular strategies to manage bloat

Set tree depth limits

Set tree node limits

Set special genetic operator rules

Add tree size to part of the fitness measure of the chromosomes

12.5. For Next Class

-

It is an evolutionary computation system/framework