18. Particle Swarm Optimization

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a stochastic population based optimization technique

Like many forms of evolutionary computation

It consists of particles that all act independently, but are influenced by the population

A flock of birds. Each bird is making decisions independently that are informed by other birds around them. As a result, it appears as if the flock is moving in some well coordinated way.

PSO is particularly well designed for real/floating point number optimization

It is relatively simple to implement compared to other forms of evolutionary computation

It has relatively few hyperparameters to tune too

Further, it is simple to extend and enhance

18.1. Particles

PSO consists of a population of particles that represent points in some search space

Like candidate solutions from a genetic algorithm

Unlike chromosomes, these particles do not have the traditional variation operators of mutation and crossover

Instead, the particles have a propensity to move towards areas that the particles likes

However, these particles are also influenced by the population of particles

They also have a propensity to move towards areas that the population likes

In terms of an optimization problem

Each particle has a propensity to move towards the best area of the search space it has encountered

While also having a propensity to move to the best part of the search space the population has encountered

Each particle also has velocity and inertia

Particles moving through a two-dimensional space moving towards, in this example, points that minimize some function \(f(x, y)\). Arrows associated with each particle represents its velocity.

18.1.1. Representation

POS is often used for real/floating point number optimization

Thus, each particle is typically represented as an \(n\) dimensional vector encoding its position in space

Where \(n\) is the dimensionality of the problem

For example, in the above figure, each particle would be represented as a two-dimensional vector

<1.42345478, -2.31345786555567>

Each particle has a

Position in space, represented as an \(n\) dimensional vector containing a position in space

\(\vec{x}(t)\) — Position at time \(t\)

Velocity, which is also represented as an \(n\) dimensional vector containing deltas

\(\vec{v}(t)\) — Velocity at time \(t\)

Best visited position (\(n\) dimensional vector)

\(\vec{p}_{best}\) — Particle’s best known position

Access to the swarm’s best known position in space (\(n\) dimensional vector)

\(\vec{g}_{best}\) — Global best known position

18.2. Velocity

The velocity determines where the particle will be for the next iteration of the algorithm

In other words, the velocity \(\vec{v}(t)\) is used to determine the position of particle \(\vec{x}(t+1)\)

18.2.1. Velocity Calculation

Velocities are typically initialized with some random values within some range

But as the algorithm executes, the velocity of the particles change as they become influenced by

The particles’ best known position in space

The population’s best known position in space

18.2.1.1. Inertia Term: \(\omega\vec{v_{i}}(t)\)

Each particle has some velocity

When particles’ velocities are being updated, the changes are applied to an already moving particle

These particles want to continue moving the way they are

They resist change

Thus, the first part of a velocity update takes into consideration the current velocity of the particle

\(\omega\vec{v_{i}}(t)\)

Where

\(i\) is some particle

\(\vec{v_{i}}(t)\) is the particle’s velocity at time \(t\)

\(\omega\) is some coefficient use to control how much the particles want to resist change

\(\omega \in [0, 1]\)

18.2.1.2. Cognitive Term: \(c_{1}\vec{r_{1}}(\vec{p_{i}}_{best} - \vec{x_{i}}(t))\)

Each particle wants to move towards the area of the search space it prefers

The best known location for that particle

Thus, part of the velocity update alters the velocity such that it will move the towards this part of the space

\(c_{1}\vec{r_{1}}(\vec{p_{i}}_{best} - \vec{x_{i}}(t))\)

Where

\(i\) is some particle

\(c_{1}\) is some coefficient used to control how much the particle is influenced by its best known position

\(c_{1} \in [0, 2]\)

The higher the \(c_{1}\), the more the particle is influenced by its best known position

\(r_{1}\) is some stochastic vector discussed below

\(\vec{p_{i}}_{best}\) is the particle’s best known position within the search space

\(\vec{x_{i}}(t)\) is the particle’s position at time \(t\)

The difference between the particle’s best known position and current position dictates where the particle needs to go

\(\vec{p_{i}}_{best} - \vec{x_{i}}(t)\)

\(c_{1}\) and \(r_{1}\) scale the vector

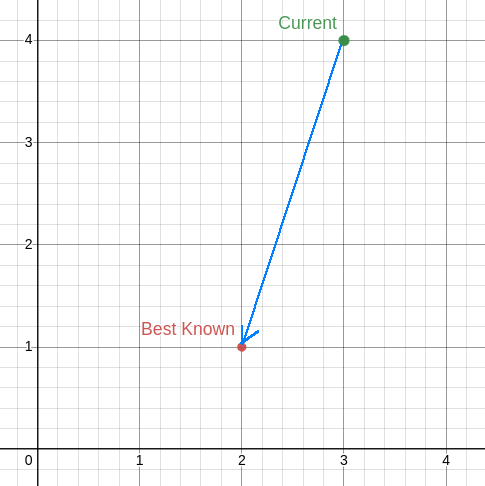

Vector (blue) showing the difference between the particle’s best known position (red) and its current position (green). The vector \((-1, -3)\) is shown starting at the current position \((3, 4)\). If the particle were to have exactly this velocity for one time step, it would return to the best known position.

18.2.1.4. Random/Stochastic Components: \(\vec{r_{1}}\) and \(\vec{r_{2}}\)

The cognitive and social portions of the velocity update included the vectors \(\vec{r_{1}}\) and \(\vec{r_{2}}\) respectively

These vectors have values between \([0, 1]\) that are stochastically determined

Randomly determined for each velocity update calculation for each particle

These random/stochastic vectors are important as they add a chance for novelty

Further, they have been empirically shown to improve the search and prevent premature convergence

18.2.1.5. Putting the Velocity Update Together

The velocity update is the sum of the parts of the update

Inertia term + cognitive term + social term

Velocity update for some particle \(i\)

As discussed, there are three coefficients that need to be tuned for the algorithm

As a starting place, van den Bergh suggests

\(\omega = 0.729844\)

\(c_{1} = c_{2} = 1.496180\)

However, one should always aim to tune these values for their needs

18.3. Position Update

After the particle’s velocity is calculated, the particle’s new position can be determined

The new position is the sum of its current position and its current velocity

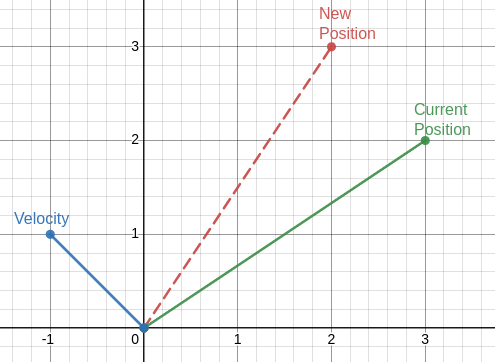

Consider the below figure

The particle’s current position \(\vec{x_{i}}(t)\) is represented as the green vector

The particle’s velocity \(\vec{v_{i}}(t+1)\) is represented as the blue vector

The particle’s new position is represented as the red dashed vector

The sum of the particle’s current position and velocity

\((3, 2) + (-1, 1) = (2, 3)\)

The summation of the particle’s current position (green) and its velocity (blue) results in the particle’s new position within the search space (red). One could also visualize this by having the velocity vector start at the end of the current position vector (instead of the origin, as it is currently shown).

18.4. Algorithm

The high-level idea of the algorithm is presented below

Initialize the particles' positions randomly

Initialize the velocities randomly

While stopping criteria is not met

For all particles

Evaluate the particle's fitness

Update particle's and global bests if necessary

For all particles

Calculate the particle's new velocity

Update the particle's position

It may not be immediately obvious, but look for the similarities between this algorithm and a genetic algorithm

Initialization

Generational loop

Fitness evaluation

Variation operations

The major differences are that

There is no real selection as all particles survive

Although, this is a selection strategy

The velocity and position updates are not mutation and crossover

However, consider the cognitive and social aspects of the velocity update

This is a mechanism for exploration and exploitation

In other words, they are in fact variation operators

18.5. Simple Enhancements

PSO’s ability to be modified is one of the reasons it’s popular

Like with most forms evolutionary computation, anything could be done

Some quick examples of some modifications are

Neighbourhoods

Each particle is part of some neighbourhood

The neighbourhood’s best is also recorded and impacts the velocity updates

\(c_{3}\vec{r_{3}}(\vec{n_j}_{best} - \vec{x_{i}}(t))\) is added to the velocity update calculation

Where \(\vec{n_j}_{best}\) is the \(j^{th}\) neighbourhood’s best known location

And \(c_{3}\) is some tunable constant and \(\vec{r_{3}}\) is another randomly determined vector

Velocity clamping

Disallow particles from having velocities over a certain value

This could be done by setting a ceiling, or an exponentially decaying velocity

Boundary/Position clamping

Dissalow particles from going beyond some boundaries

One could just set a limit and not allow particles beyond it

More creative strategies include having particles jump to the other side of the space

Or have the particles bounce off the boundary back in the other direction

Charged PSO

Particles repel one another

The velocity update includes a term for the particles’ propensity to move away from one another

18.6. For Next Class

Check out the following script

18.2.1.3. Social Term: \(c_{2}\vec{r_{2}}(\vec{g}_{best} - \vec{x_{i}}(t))\)

Similarly, each particle is influenced by the population’s best known position

Where