6. Overview

Given a population of individuals within an environment with limited resources

Competition for those resources occurs

This competition causes natural selection

This causes the overall fitness of the population to rise

An evolutionary “arms race”

In the context of Evolutionary Computation (EC)

Given some problem and a mechanism for measuring solution quality

The problem is the environment

Generate a fixed size population of solutions to the problem

The fixed sized population is the limited resource

Apply the quality measure to the solutions

More fit solutions reproduce to fill the next generation’s population

More fit individuals compete better

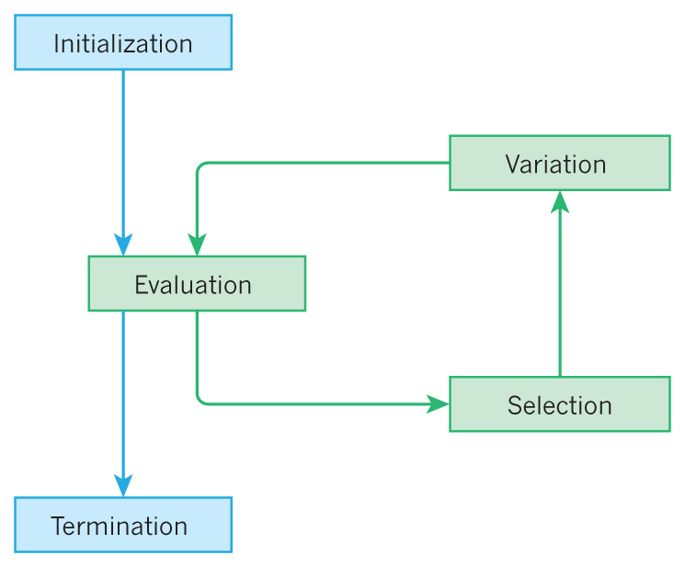

High-level idea of most evolutionary computation algorithms.

There are two big forces at play

Variation

Genetic operators like mutation and crossover

Increases population diversity

Pushes the population towards novelty

Selection

Surviving within the population

Decreases population diversity

Pushes the population towards quality

6.1. Types of Evolutionary Computation

Given how flexible the framework of EC is, there is a large and growing list of types

Their differences often come down to specific details, their encodings, and types of problems they are designed for

But they are all population-based iterative processes with selection and variation mechanisms

Common popular EC algorithms are

Genetic Algorithms

Typically have a string or array/list encoding

Evolutionary Strategies

Works well with real numbers

Differential Evolution

Works well with real numbers

Does not use a gradient/problem does not need to be differentiable

Particle Swarm Optimization

Works well with real numbers

Evolutionary Programming

Evolves finite state machines

Genetic Programming

Evolves programs

Typically encoded as a tree structure

6.2. Components

Evolutionary computation algorithms are remarkably modular so they can have as many components as desired

The core components are discussed below at a high-level

6.2.1. Representation

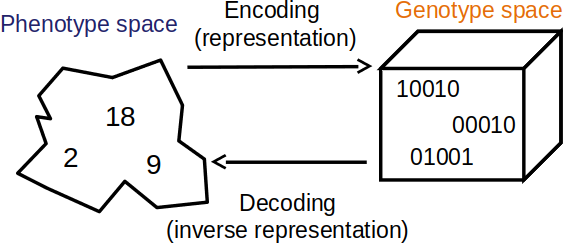

The representation is how the problem is encoded

The genotype is the encoding

The phenotype is what the encoding means in the context of the problem

Visualization of the genotype and phenotype spaces. In this example, the phenotype space consists of integers while the genotype space encodes integers as unsigned binary numbers.

Candidate solution, phenotype, and individual are words used to describe a possible solution to a problem

Genotype and chromosome are words used to describe an encoding of a possible solution to a problem

However, chromosomes are themselves candidate solutions

“Candidate solution” is often used as a catch-all term

Locus, position, gene, and allele are words used to describe a part of the chromosome

Although, this jargon is not commonly used in practice

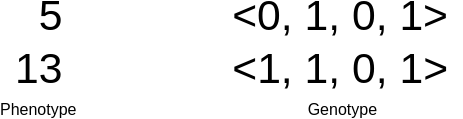

Two phenotypes and genotypes for the unsigned binary number maximization problem discussed previously. In this example, the binary number being maximized is 4 bits. The phenotype is the actual integer and the genotype is the binary string. Here, the binary string is shown as a vector. An locus/position/gene/allele would be a single value within the vector (genotype).

It is often ideal to ensure all possible valid solutions can be represented in the genotype space

Constraining the search space by eliminating inadmissible solutions can greatly improve performance

What the encoding for a given problem should be is not always obvious

A clever encoding can drastically improve the results of the algorithm

These ideas are discussed further in a future topic

6.2.2. Fitness and Fitness Function

The fitness is the measure of how good a given candidate solution is

The fitness function is a mechanism for measuring a given candidate solution’s goodness

This is what the population is trying to adapt to

What the fitness function should be is not always straightforward

Like representation, the choice of fitness function can drastically impact the performance of the algorithm

Consider the unsigned binary number problem discussed in a previous topic

Two different fitness functions were used

The actual integer value of the unsigned binary number

The number of ones in the unsigned binary number

Although both fitness functions worked on the same representation, the fitness function impacted the performance

It altered how the population traversed the genotype space

6.2.3. Population

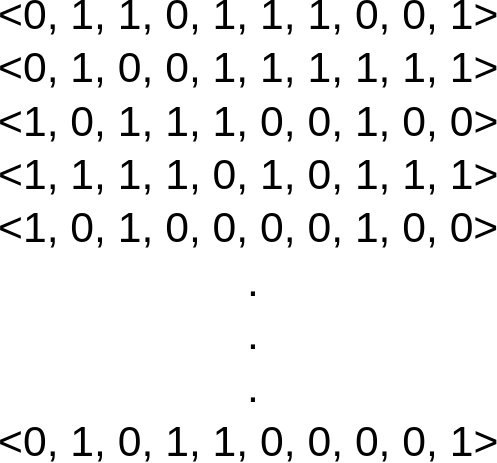

A population is a collection of chromosomes

Each chromosome would have a fitness value associated with it

The population typically has a fixed size, which is the limited resource for the candidate solutions to compete for

Over time, the population’s average fitness should improve

Diversity is a measure of how different the candidate solutions are within the population

It is often helpful to think of the population evolving rather than individual candidate solutions

Population for the unsigned binary number maximization problem discussed previously. In this example, the binary number being maximized is 10 bits. The population is a collection of chromosomes.

6.2.4. Selection

Selection is a mechanism for selecting candidate solutions for reproduction and/or entering to the next generation

Selection is stochastic, but probabilistic

More fit candidate solutions have a higher chance to be selected

There are many ways to perform selection, but two popular strategies are:

Roulette Wheel

Tournament

These strategies will be discussed further in a later topic

6.2.4.1. Generational vs. Steady State

There are two popular strategies for running the evolutionary computation algorithms

Generational

Steady State

Generational will have discrete generations where selection occurs to fill a whole new population for each generation

The previously discussed unsigned binary number maximization problem’s GA was generational

Steady state does not have discrete generations

Instead, these operate continuously on the same single population

They select candidate solutions for reproduction and selects candidates for replacement

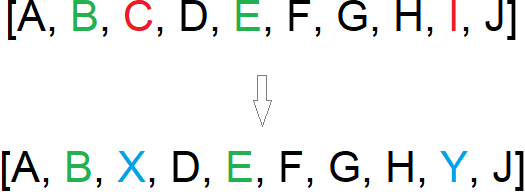

The offspring will replace the candidate solutions selected for replacement

Example of a round of selection occurring in a steady state evolutionary algorithm. The list represents a population and the individual letters represent individual chromosomes. Here, chromosomes “B” and “E” (green) are selected for reproduction and chromosomes “E” and “I” (red) are selected for replacement. The offspring chromosomes of “B” and “E”, denoted as “X” and “Y” (blue), replace “E” and “I” within the same population.

6.2.5. Variation Operators

Variation operators are used to create new, but different, individuals based on old ones

Depending on the representation, some variation operators may be more helpful than others

Although it depends on the specific type of evolutionary computation algorithm used, there are typically two types

Mutation

Crossover

6.2.5.1. Mutation

Acts on a single chromosome

Small changes

Stochastic changes

Stochastic chance to happen

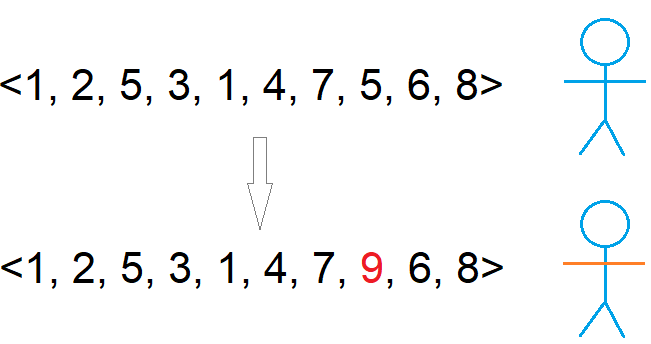

Typically destructive

Example single point mutation. The vector is some integer encoding that represents the blue stick figure phenotype. A single element in the vector is changed which causes the phenotype to change slightly; the arms of the stick figure changed colour to become orange.

6.2.5.2. Crossover

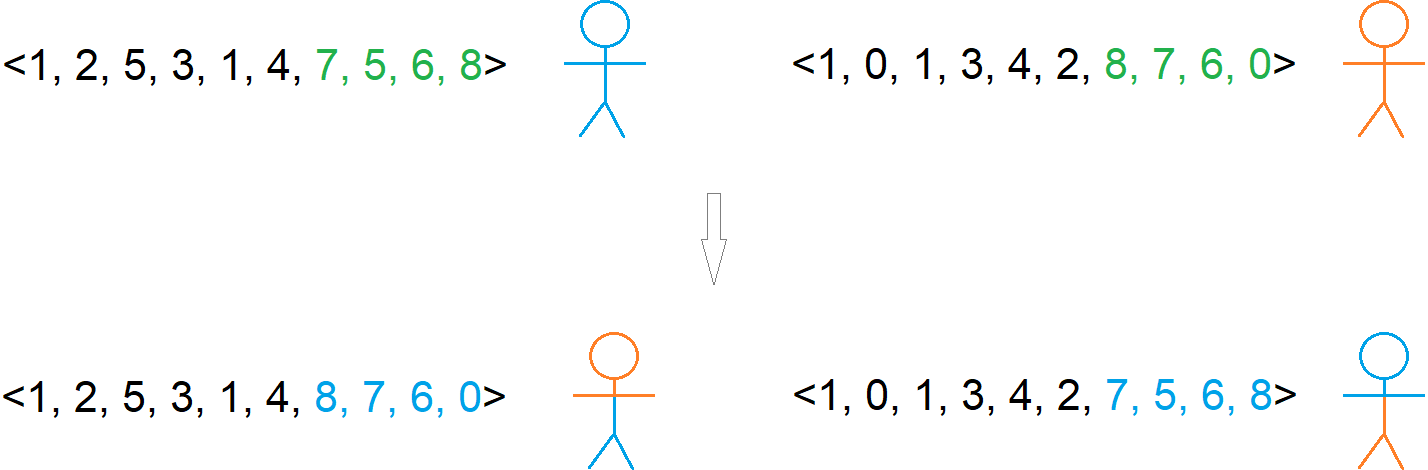

Acts on two chromosomes

The idea is, if both parents are good, then perhaps their offspring will also be good, but different

Stochastic change

Stochastic chance to happen

Example single point crossover. The top vectors represent the chromosomes and their corresponding stick figure phenotypes selected for crossover. The last four elements within the vectors are exchanged to produce the offspring. This caused the children to inherit traits from both parents.

6.2.6. Initialization and Termination

The initial population is often randomly generated

Sometimes the initial population can be seeded with already known high-quality solutions

However, this can have a negative impact as the search may get stuck in a local optimum due to lack of diversity

Termination can be done however the user wants

After a predetermined number of generations

After a desired fitness value is achieved

After some diversity threshold is met

If fitness has not improved for some time

6.3. Example

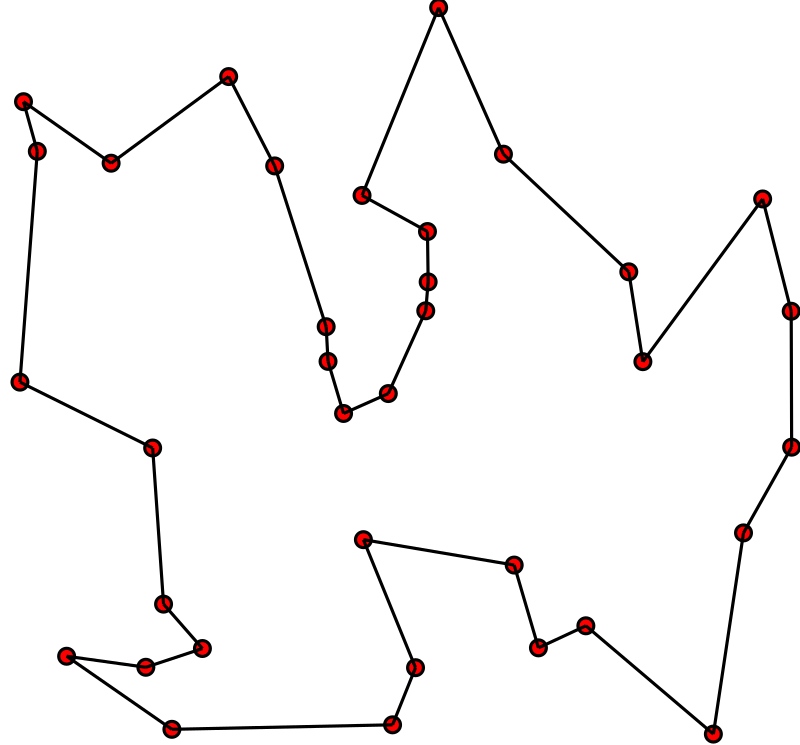

Consider the Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Find the shortest Hamiltonian cycle in some weighted graph

A Hamiltonian cycle representing a solution to a TSP. Black lines represent the pathway and the red vertices represent the cities. This instance assumes the graph is completely connected and the distance between vertices is the Euclidean distance.

Consider what the parts of the GA would be for this problem

6.3.1. Representation

The phenotype is the Hamiltonian cycle

For the genotype, an ordered collection of cities could represent the path

Or, more simply, by assigning each city some integer, it could be an ordered collection of integers

Between \(0\) and \((n-1)\), where \(n\) is the number of cities

This would make the search space every combination of integers between \(0\) and \((n-1)\)

\(<0, 0, 0, ..., 0>\)

\(<0, 0, 0, ..., 1>\)

\(<0, 0, 0, ..., 2>\)

\(...\)

\(<(n-1), (n-1), (n-1), ..., (n-1)>\)

This would mean there are a total of \(n^{n}\) possible combinations

There are \(n\) possible integers for each of the \(n\) possible spots in the collection

That’s a lot…

However, this would include many inadmissible solutions since each city should be visited once and only once

Except for the starting city, which is visited twice since it is started and ended on

This knowledge can be taken advantage of

Instead, a permutation of the integers from \(0\) to \((n-1)\) could be used

This would ensure each city is visited once and only once

To analyze the size of the search space, consider the number of permutations there are of the \(n\) cities

There are a total of \(n\) possibilities for the first index

After that, there are a total of \(n-1\) possible cities to visit

Then \(n-2\), then \(n-4\), and so on

Thus, there a total of \(n \times (n-1) \times (n-2) \times ... \times 2 \times 1\) permutations

Which can be written as

Therefore, the search space has a size \(n!\)

This is still a very large number, but it is an improvement over \(n^{n}\)

Ultimately however, the representation can be whatever, but being clever about the encoding can impact the performance

6.3.2. Population

Whatever encoding is used, the population would simply be a collection of coded values

With the permutation representation, the population would be a collection of permutations of length \(n\)

6.3.3. Fitness

The phenotype is the actual Hamiltonian cycle

The genotype is encoding a Hamiltonian cycle as a permutation

The fitness would be the total length of the Hamiltonian cycle

Given a chromosome, sum up the distances between the cities in order

Being sure to include the distance from the last visited city back to the starting city

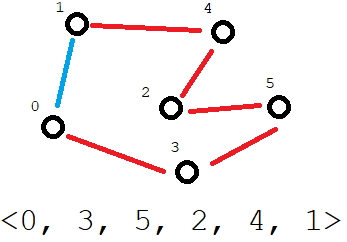

Chromosome and it’s meaning as a Hamiltonian cycle in some graph. The fitness is the sum of the length of all the distances between adjacent values in the chromosome’s permutation (red edges) plus the distance from the last city back to the first (blue edge).

This provides a nice gradient to follow when traversing the search space

But not all improvements will necessarily be a step towards the optimal solution

6.3.4. Variation Operators

Which variation operators are used depends on the representation

But ultimately the choice can be whatever, but it will impact performance

For the permutation representation, a simple single point mutation will not work well

Selecting one city and replacing it with another will not work since it would break the permutation

For example, consider this permutation of seven cities \(<0, 5, 3, 4, 2, 6, 1>\)

Replacing the city at index

3(city \(4\)) with any value other than \(4\) would break the permutationIt would cause city \(4\) not to be visited and some other city to be visited twice

Instead, a swap mutation could be used

Select two indices and swap the cities between them

Similarly, for crossover, a simple one-point crossover will not work as it could break the permutation

For example, consider \(<0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6>\) and \(<6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0>\)

Performing one-point crossover at any index other than index

0would break the permutation

Instead, a more complex crossover, such as partially mapped crossover or order crossover, would need to be used

These are discussed in more detail later in the course

6.3.5. Selection

There are so many possibilities for selection

For simplicity, tournament selection could be used

Randomly select \(k\) candidate solutions

Select the best candidate solution of the \(k\) based on fitness

Repeat

If a generational algorithm is used, this would be repeated until the new population is full

If a steady state algorithm is used, chromosomes would need to be selected for replacement

There are many ways this could be done

Replace based on age

Replace based on fitness

Replace randomly

6.3.6. Initialization and Termination

For initialization, for both encodings, randomly generate the chromosomes would work

For termination, just run for some predetermined number of generations

6.4. Typical Settings

Evolutionary computation algorithms have several hyperparameters to set

How many there are will depend on the specific type

For a generational GA using tournament selection that will run for some number of generations

Number of generations

As big as it needs to be

Could be in the hundreds or the billions

Population size

Could be a few dozen or in the thousands

Crossover rate

Usually around 80%

Mutation rate

Usually around 10%

Tournament size

Usually around 2 to 5, but depends on the population size

Although some specific values are mentioned above, all settings determined with some trial runs

The above examples are numerical parameters

But it’s not just the numbers associated with certain parameters

Given the modularity of evolutionary computation algorithms, there is a lot of choice in what is used

For example, the generic operators, representation, and selection strategy used

These are called symbolic parameters and often have numerical parameters associated with them

For example, tournament size for tournament selection

6.5. Typical Behaviour

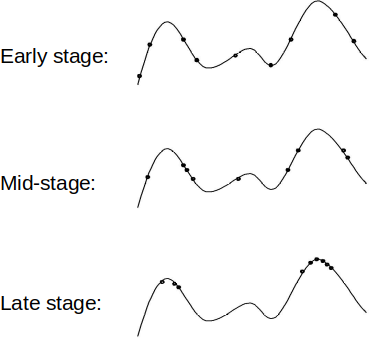

With a randomly generated starting population, the population will be spread throughout the search space

Over time, the population will start to converge on relatively good areas of the search space

As more time passes, the population will ideally converge to even better areas of the search space

Typical distribution of populations over the course of evolution. This example is of a one dimensional problem with the search space defined by the curve. All possible values for the problem are along the x-axis and the corresponding fitness values are along the y-axis. Candidate solutions within the population are represented as points on the curve.

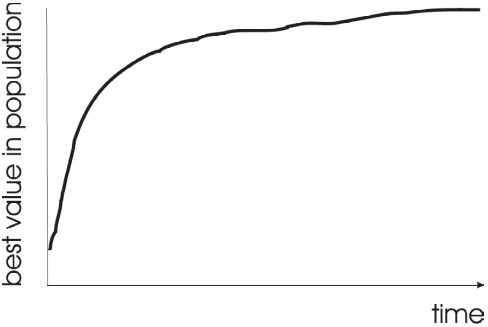

The fitness of the population will improves over time

But as time goes on, the rate in which the fitness improves will slow

Typical learning curve of an evolutionary computation algorithm. Early in the search, rapid improvements to fitness will happen, but as time goes on the improvements will slow and the search will begin to converge.

Changing the values of the parameters will often impact the shape of the learning curve

Learning curves are helpful for tuning the hyperparameters

6.6. Final Notes

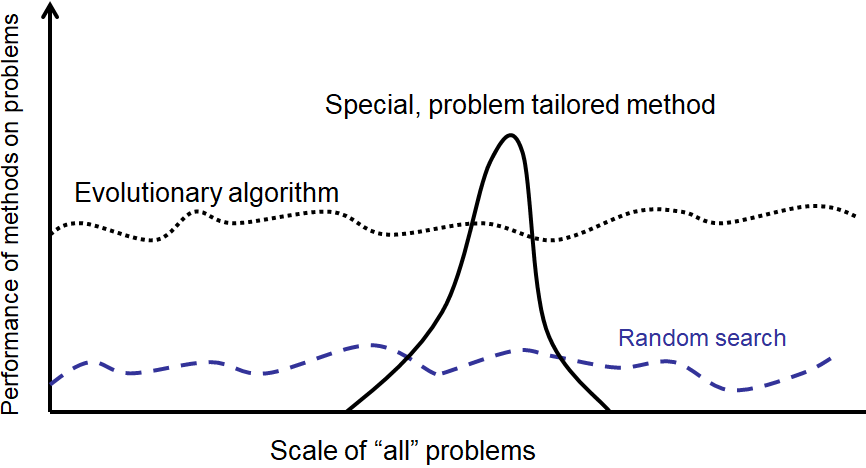

Realistically, when trying to solve a problem, it is not ideal to use evolutionary computation

It is computationally expensive

Overfits

Hard to understand why it came up with what it did

Will often not find the best solution to a problem

However, it is widely accepted that some problems have no tractable solution

If finding the best solution is not practical, a good solution will work

Thus, sometimes, when all else fails, it’s one of the best tools available

Further, evolutionary computation algorithms are population based, meaning at the end, a suite of results are obtained

They tend to work well on noisy data

They tend to work well on large and noncontinuous search spaces

They often require minimal expertise in a subject area to find good results

High-level idea of evolutionary computation algorithms’ performance on arbitrary problems. Although they perform well in general, a well designed algorithm for a particular problem will typically perform much better.

The point is, if an effective and tractable algorithm for a problem exists, use it

If all out of ideas, give evolutionary computation a try

6.7. For Next Class

TBD