19. Control Logic

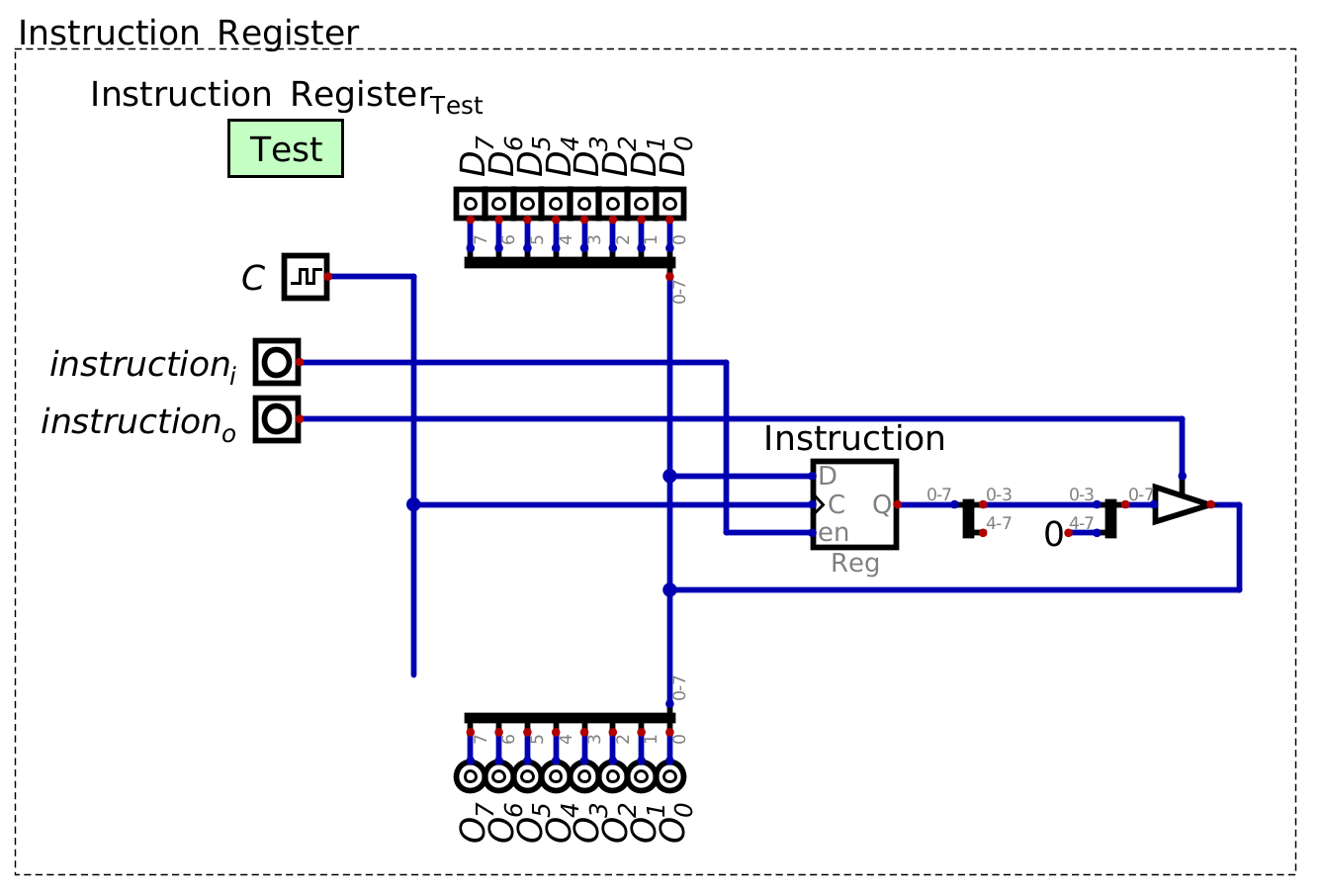

Instructions are fetched and put into the instruction register for processing

An instruction set has already been defined

Each instruction’s microcodes are known

How the hardware is manipulated for each instruction

However, there is still no way for the system to manipulate its own control logic

There is no way for the system to take an instruction and then activate/deactivate the various hardware modules

In other words, how can the system know how to physically perform an instruction?

19.1. Instruction and Microcode Steps

The instruction register stores the operator and operand of the current instruction. The operand is output to the bus for use during the execution of the instruction. The operator remains in the register for processing.

Consider what is stored in the instruction register and what is being output

The operator, specifying some instruction to execute

The most significant four bits in the instruction

The operand, specifying some data for use in execution of the specific instruction

The least significant four bits in the instruction

As previously discussed, each instruction requires several steps

For example, loading data into register A from RAM (

LDAR/0001)Output the operand from the instruction register and put it into the address register

Output the value from the specified RAM address to the A register

Additionally, before any processing of any instruction can occur, it must be fetched from RAM

No matter what instruction is to be executed, the two steps in the fetch cycle must happen

In other words, instructions require several steps

19.1.1. Microcode Counter

The operator can be used to specify the steps to be executed in order to perform the instruction

The operator would manipulate the control signals for the system

Thus, a look up table can be used to find the steps required to perform the full instruction

Input to the look up table is the operand, output is the control signals

However, there is a problem with this idea since instruction may require several sequential steps too complete

The microcodes

Consider the below table of the 4 microcode steps required for loading data from RAM to register A

The first two steps are the fetch cycle

The latter two steps move dara from the specified RAM address to register A

\(Address\) |

\(RAM\) |

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

\(ALU\) |

\(out\) |

\(PC\) |

\(Instruction\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not all instructions require 4 steps

1 instruction (

NOOP) takes 2 microcode steps (fetch only)Six instructions take 3 steps

Six instructions take 4 steps

For simplicity and consistency, consider each instruction as a group of 4 steps

Below is a table of the microcode steps of the first 3 instructions in the instruction set

NOOPLDARLDAD

Operator |

Microcode Step |

Control Logic |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Program Counter -> Address Register |

|

|

|

RAM -> Instruction Register, Enable Program Counter |

|

|

|

Nothing |

|

|

|

Nothing |

|

|

|

Program Counter -> Address Register |

|

|

|

RAM -> Instruction Register, Enable Program Counter |

|

|

|

Instruction Register -> Address Register |

|

|

|

RAM -> Register A |

|

|

|

Program Counter -> Address Register |

|

|

|

RAM -> Instruction Register, Enable Program Counter |

|

|

|

Instruction Register -> Register A |

|

|

|

Nothing |

|

… |

… |

… |

Each operator specifies a grouping of microcodes

Each microcode can be identified by the microcode step count

Considering the operand and microcode step together, there is a unique identifier for each instruction’s microcode

A unique six bit identifier

Four bits for the operator, two for the microcode step

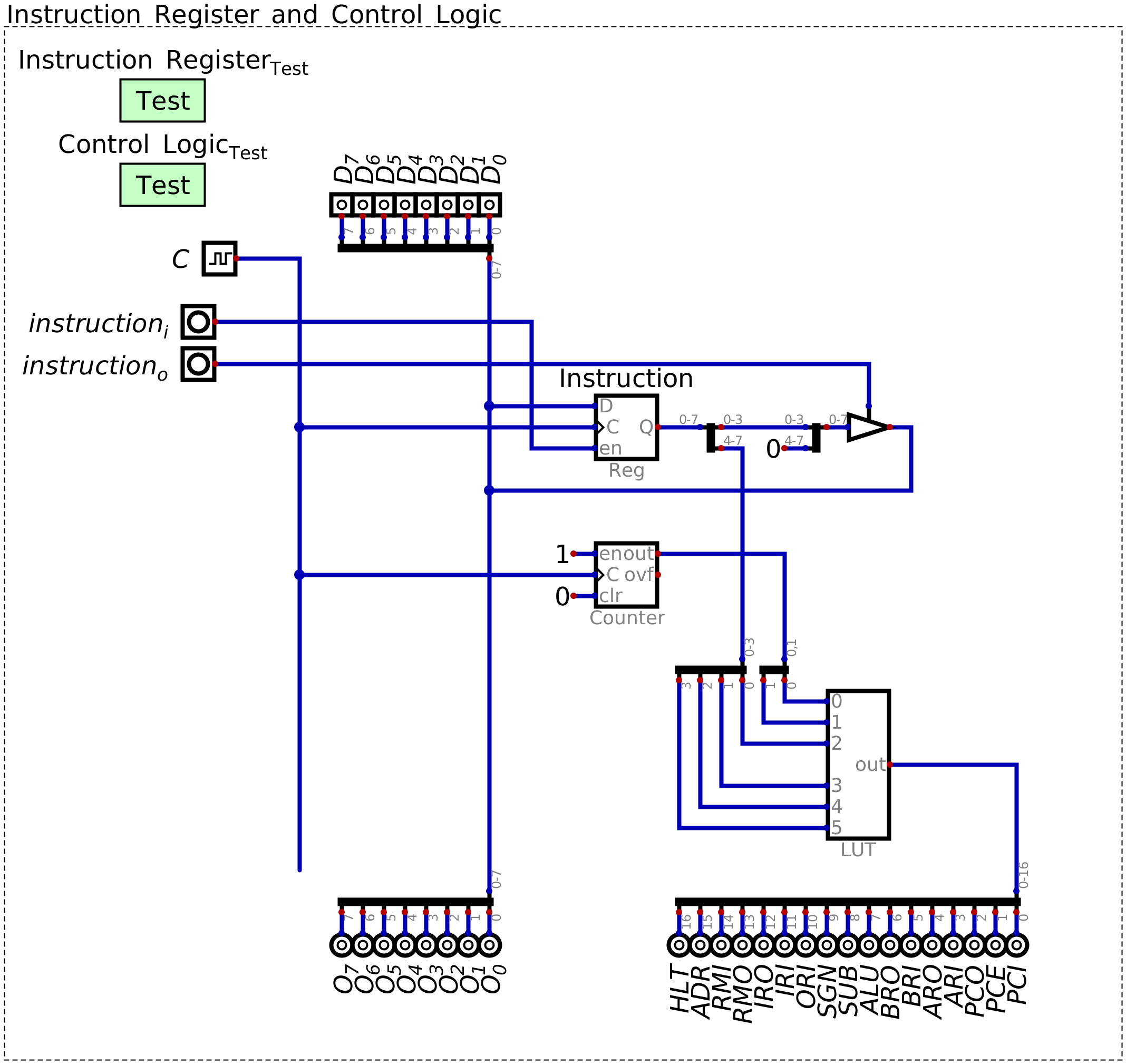

Therefore, given a mechanism to keep track of the microcode step, a look up table may still be used

Map the operand + microcode counter to the control logic for the specific microcode step

Fortunately, there is a simple way to keep track of the microcode steps — a counter

Like the program counter

This counter will be referred to as the microcode counter

Operator from the instruction register and microcode step count from the microcode counter used as input to a look up table containing the control signals. The input to the look up table would map to the control signals for the specific operator’s current microcode step.

Unlike the program counter, this microcode counter will count at every clock pulse

The program counter only counted when enabled since each individual instruction may take several clock pulses

The microcode counter keeps track of each microcode step, each taking one clock pulse

Note

Since several instructions takes less than four clock cycles, one may have noticed that the system would be wasting clock cycles; the system would be doing nothing for a clock pulse. What are some ways this could be addressed?

19.2. Look Up Table to Process Instruction

Given the 16 instructions, each with 4 microcode steps, there are a total of 64 rows in the look up table

Each of these rows contains binary patterns controlling many control signals

One could write out the look up table by hand, but this would be tedious

Therefore, a script will be create to programmatically generate the hex file for the look up table

Similar to how it was done for the seven segment display patterns

With the current configuration of the ESAP system, a total of 17 control signals exist

Therefore, the look up table will have a 17 bit output where each bit corresponds to a specific control signal

Below is a series of constants labelling each of the 17 bits

36HLT = 0b1_00000000_00000000

37ADR = 0b0_10000000_00000000

38RMI = 0b0_01000000_00000000

39RMO = 0b0_00100000_00000000

40IRO = 0b0_00010000_00000000

41IRI = 0b0_00001000_00000000

42ORI = 0b0_00000100_00000000

43SGN = 0b0_00000010_00000000

44SUB = 0b0_00000001_00000000

45ALU = 0b0_00000000_10000000

46BRO = 0b0_00000000_01000000

47BRI = 0b0_00000000_00100000

48ARO = 0b0_00000000_00010000

49ARI = 0b0_00000000_00001000

50PCO = 0b0_00000000_00000100

51PCE = 0b0_00000000_00000010

52PCI = 0b0_00000000_00000001

Here, the most significant bit of the 17 output bits controls the \(Halt\) signal

\(Halt\) has yet to be discussed, but will deactivate the system’s clock, thereby halting the program

The least significant bit controls the \(PC_{i}\) signal

The actual order of these signals does not really matter

The fact that \(Halt\) is the most significant bit is by no means necessary

All that matters is that each signal connects to the corresponding module in the ESAP system

Here, the order is set for visual clarity and symmetry of the control bus

With these constants set, one can easily create microcodes by performing bitwise

ORon the constantsFor example, to create the microcode for “Instruction Register -> Address Register” —

IRO|ADRThis creates the full 17 bit binary pattern to activate the corresponding modules for the microcode

IRO|ADR0_00010000_00000000 | 0_10000000_000000000_10010000_00000000

Each of the 16 instructions will be a collection of up to 4 groups of specific constants

ORed togetherBelow, the instructions are stored in a list of 16 lists of length 4

Each list of length 4 corresponds to the 4 microcodes for a specific instruction

Each of the 16 lists of length 4 corresponds to a specific instruction

60INSTRUCTIONS = [

61 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, 0, 0 ], # 0b0000 --- 0x0 --- NOOP --- No Operation

62 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, RMO|ARI ], # 0b0001 --- 0x1 --- LDAR --- Load A From RAM

63 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ARI, 0 ], # 0b0010 --- 0x2 --- LDAD --- Load A Direct

64 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, RMO|BRI ], # 0b0011 --- 0x3 --- LDBR --- Load B From RAM

65 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|BRI, 0 ], # 0b0100 --- 0x4 --- LDBD --- Load B Direct

66 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, ARO|RMI ], # 0b0101 --- 0x5 --- SAVA --- Save A to RAM

67 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, BRO|RMI ], # 0b0110 --- 0x6 --- SAVB --- Save B to RAM

68 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, ALU|ARI, 0 ], # 0b0111 --- 0x7 --- ADAB --- Add B to A

69 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, ALU|SUB|ARI, 0 ], # 0b1000 --- 0x8 --- SUAB --- Subtract B from A

70 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|PCI, 0 ], # 0b1001 --- 0x9 --- JMPA --- Jump Always

71 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, 0, 0 ], # 0b1010 --- 0xA --- NOOP --- No Operation

72 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, 0, 0 ], # 0b1011 --- 0xB --- NOOP --- No Operation

73 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, 0, 0 ], # 0b1100 --- 0xC --- NOOP --- No Operation

74 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, RMO|ORI ], # 0b1101 --- 0xD --- OUTU --- Output Unsigned Integer

75 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, IRO|ADR, RMO|ORI|SGN ], # 0b1110 --- 0xE --- OUTS --- Output Signed Integer

76 [PCO|ADR, RMO|IRI|PCE, HLT, 0 ], # 0b1111 --- 0xF --- HALT --- Halt

77]

Notice that each of the 16 instructions start with the same two microcodes

PCO|ADRandRMO|IRI|PCEThese are the two microcodes of the fetch cycle

This way, no matter what operator value is in the instruction register, fetch happens the same way

With all microcodes set for each instruction, the list of instructions can be written as hex values to an output file

99with open("control_logic_patterns_for_look_up_table.hex", "w") as hex_file:

100 hex_file.write("v2.0 raw\n")

101 for instruction in INSTRUCTIONS:

102 hex_file.writelines(f"{hex(microcode_pattern)}\n" for microcode_pattern in instruction)

This file can be loaded into the control logic’s look up table

With this, the look up table can now map the input (operator + microcode step) to the 17 bit control signal pattern

Control logic look up table outputting the 17 control signals for the four microcode steps of the instruction

0001 (LDAR).

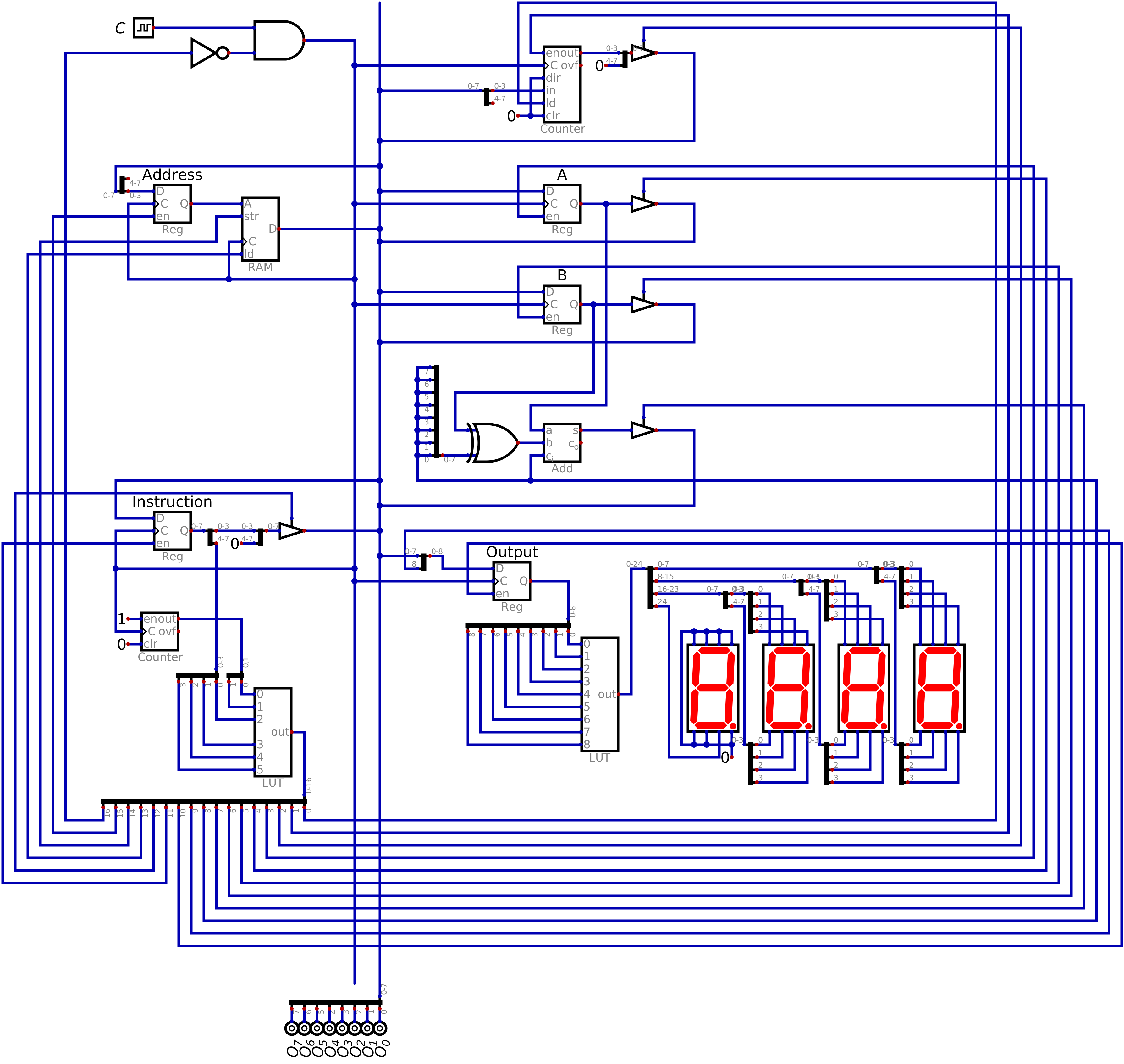

19.3. Including the Control Logic Module in the System

Adding the control logic look up table to the system requires a reconfiguration of the control signals

The toggles for each control signal is removed as each signal is connected to the output of the look up table

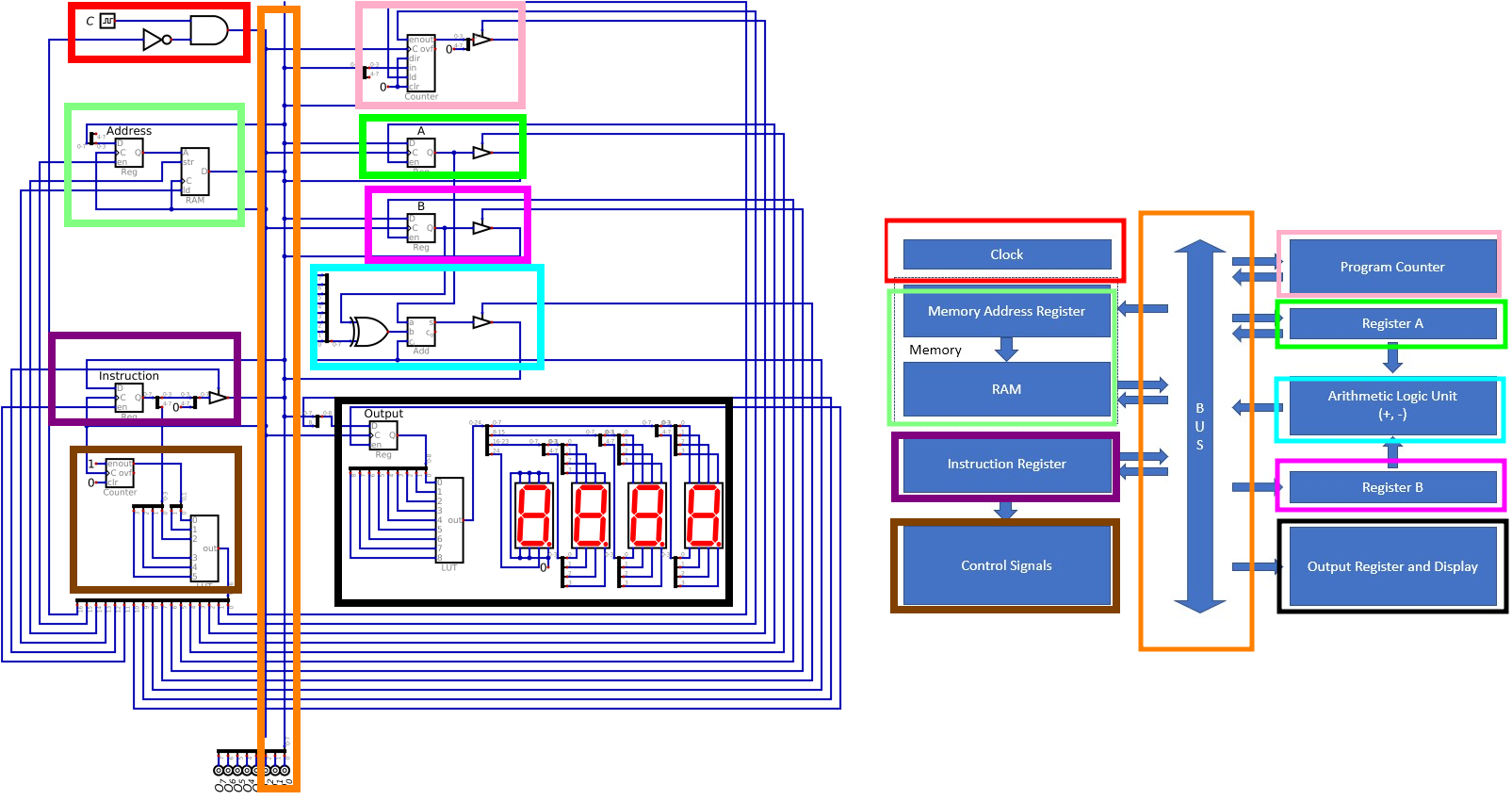

Configuration of the ESAP system with the ALU, RAM, output, program counter, instruction register and control logic modules connected.

In addition to connecting the control signals, logic was added to the system to control when the clock is active

This allows for the \(Halt\) signal to halt the system

When \(Halt\) is high, the clock is disabled

This is achieved by inverting the \(Halt\) signal and

ANDing it with the clock signal

Further, the data input toggles were removed from the top of the bus since there is no need for them anymore

All data the system needs will be programmed into RAM

There will be no need to add data to these lines while the system is running

Comparison of the current system with the control logic and the ESAP architecture overview.

19.4. For Next Time

Something?