10. The Bus

The bus physically connects several components within a computer

It facilitates the transfer of information between these components, such as RAM and registers

Typically, there are three types of busses

Data bus — Transfer data between components

Address bus — Transmits memory addresses

Control bus — Sends signals responsible for controlling when components are active

10.1. Tri-State Logic

Tri-state logic was discussed in the previous topic when introducing drivers

Drivers were used to control RAM out

Briefly, components can have three different states

Output a high signal by connecting the line to some voltage source (

1)Output a low signal by connecting the line to ground (

0)High impedance state/do nothing (

Z)

For a shared signal line like a bus, it is important that only one component is outputting a value at a time

Outputting

0is not the same as outputting nothing since any other signal on the same line would be sunk to groundIn other words, if two components are connected to the same output line

If one component outputs

0by connecting the line to groundAnd the other outputs

1by connecting the line to a voltage sourceThe line would ultimately have no voltage as it would be connected to ground

As an analogy, consider a long sink with several faucets and drains connected to it

A long sink representing some signal line with several components connected. Here, the sink itself represents the line and the faucet/drain represents the component’s connection to the shared line.

Here, the sink represents some shared signal line that several components can connect to

The components’ connections to the signal line are represented by the faucets and corresponding drains

If a components is outputting a signal to the shared line, the faucet will either be on, or the drain will be open

When the output is

1, the faucet will be on adding water to the sinkWhen the output is

0, the drain will be opened, allowing any residual water to drain from the sink

All other components will be left alone (

Z), with neither the faucet on or the drains openedThe presence or absence of water in the sink means that the signal is high or low, respectively

Consider what would happen in this analogy if one tried to use

0to mean nothingIf one of the components had their faucets on, but others had their drains open, the water would immediately drain

The sink would remain empty

This would be a problem since the sink should have water in it

This is why it’s important to have a third state

10.2. Connecting Components

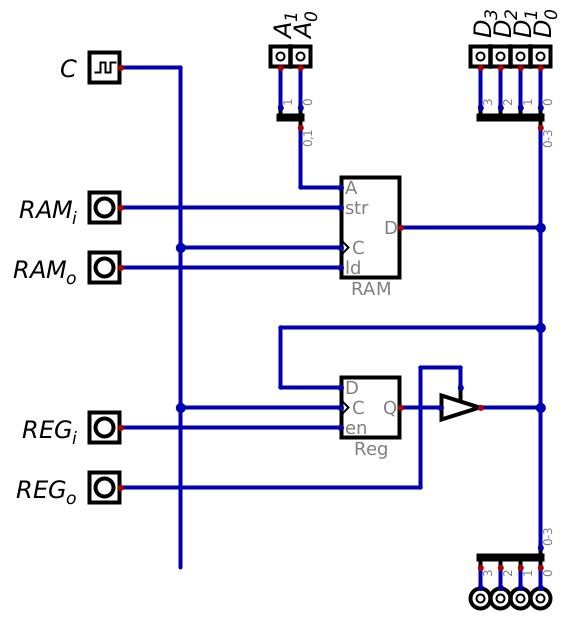

RAM and a register connected to various busses. This configuration allows for inputting data into the bus from an external source (the input buttons), controlling the memory address used in RAM, and controlling when the RAM and register components are inputting/outputting data.

Above is a RAM component connected to a register component via a data bus

With this configuration, data can be input into the system via the input buttons

The memory address the RAM component is referencing is controlled by address input buttons

Finally, the components are controlled by turning on/off their inputs and outputs

Notice how the register only has an input enable on the component

To control the register’s output, a driver is added after the register’s output

Here, how the components’ signal lines are connected is important, not the actual physical layout of the components

The location of each component in the layout is arbitrary

Within this layout are three physically separate busses

The data bus

For transferring data between components

In this configuration, there are four data lines, but more could be added

Here, data can be inputted into the system via the buttons labelled \(D_{0}\) through \(D_{3}\)

The data buttons are tri-state to provide a way to not input any value from an external source

The outputs at the bottom is there so one can see what value is on the bus at any given time

The address bus

For controlling which memory address in RAM is currently being used

Here, for simplicity, there are two address lines, meaning only four memory addresses can be accessed from RAM

These are controllable via the buttons labelled \(A_{0}\) and \(A_{1}\)

The control bus

Controls when individual components are reading from or writing to the data bus

Here, each is labeled with an \(i\) or \(o\) signifying input or output

Below is an image of the layout with the busses identified

Configuration of a RAM component and a register component connected to various busses. These data bus is shown within the green box on the right, the address bus is the yellow box in the top centre, and the control bus is shown by the pink box on the left.

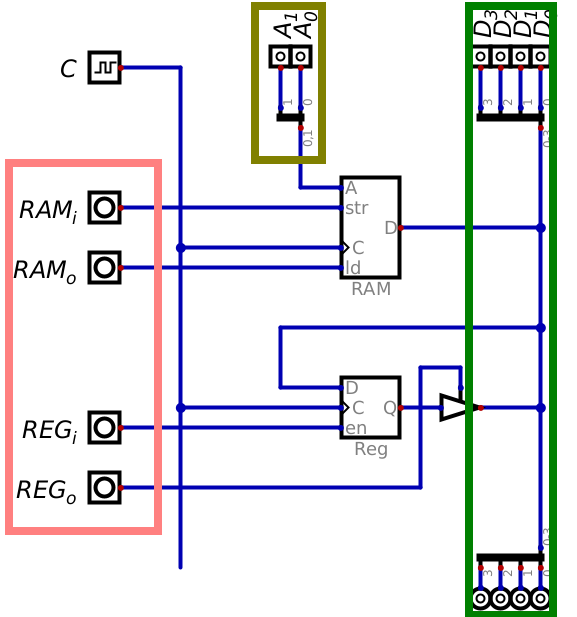

10.3. Loading Data into RAM

Consider how one would add data to RAM

This would require manipulating the signals along the three busses in a specific way

This is probably best explained with an example

Add the value

0001to memory address00and1000to memory address01Below is a table showing how the signals would need to be set to achieve this

This table however is not a truth table, but instead represents what is effectively a program

In the below table,

Cmeans clock pulse, which would happen only after all other signals are set

\(RM_{i}\) |

\(RM_{o}\) |

\(RG_{i}\) |

\(RG_{o}\) |

\(A_{1}\) |

\(A_{0}\) |

\(D_{3}\) |

\(D_{2}\) |

\(D_{1}\) |

\(D_{0}\) |

\(C\) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

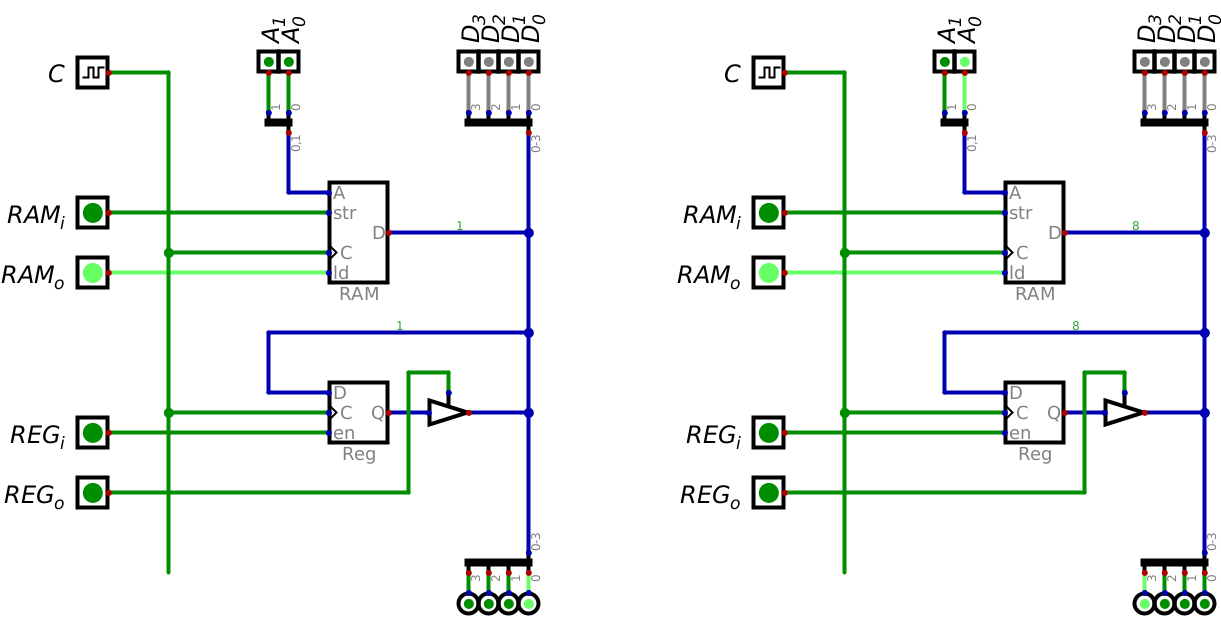

The left image shows how the signals should be set to add the value 0001 to memory address 00, and the right

shows how they should be set to add the value 1000 to memory address 01. A clock pulse would be required in

both scenarios to have the data be stored in RAM. These images correspond to the two rows in the above table.

If one wants to verify that the data did in fact get stored, a different set of signals is needed

The data stored in RAM would be displayed on the outputs at the end of the data bus

Be mindful that the data input lines need to be set to

Z, otherwise their inputs will interfere with RAM’s outputClock pulses are not actually needed here, but are included in the table for completeness

\(RM_{i}\) |

\(RM_{o}\) |

\(RG_{i}\) |

\(RG_{o}\) |

\(A_{1}\) |

\(A_{0}\) |

\(D_{3}\) |

\(D_{2}\) |

\(D_{1}\) |

\(D_{0}\) |

\(C\) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

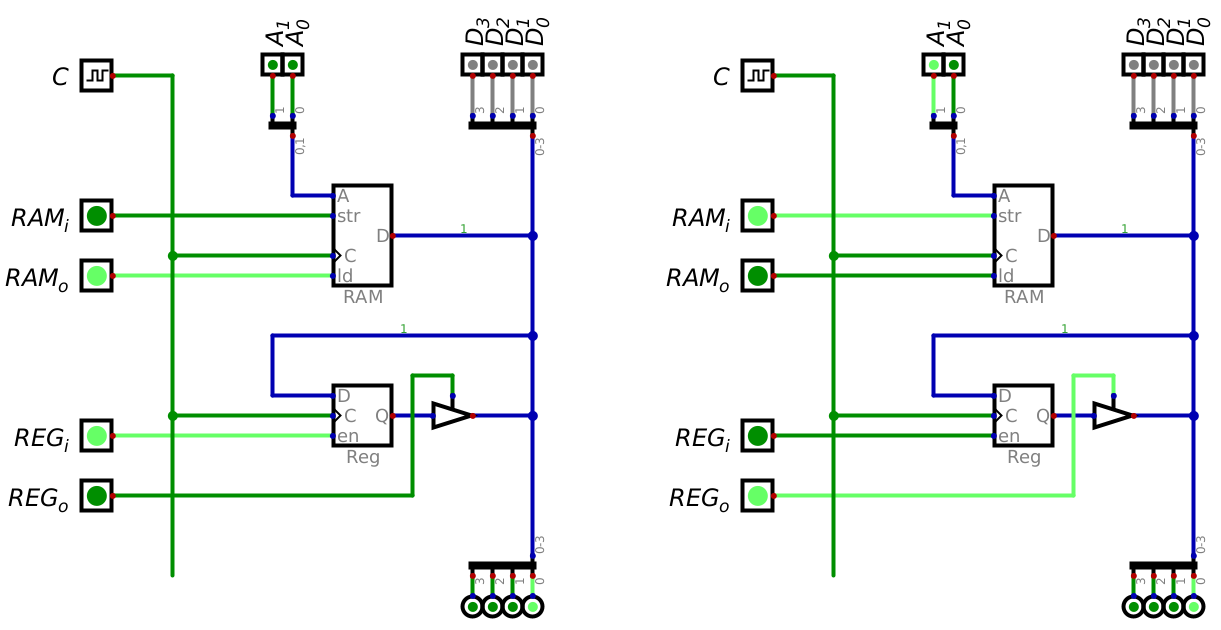

The left image shows how the signals should be set to verify that the value 0001 is stored in memory address

00, and the right shows how they should be set to verify that the value 1000 to memory address 01. These

images correspond to the two rows in the above table. The data stored in RAM at the specified memory addresses is

displayed on the output at the bottom of the data bus.

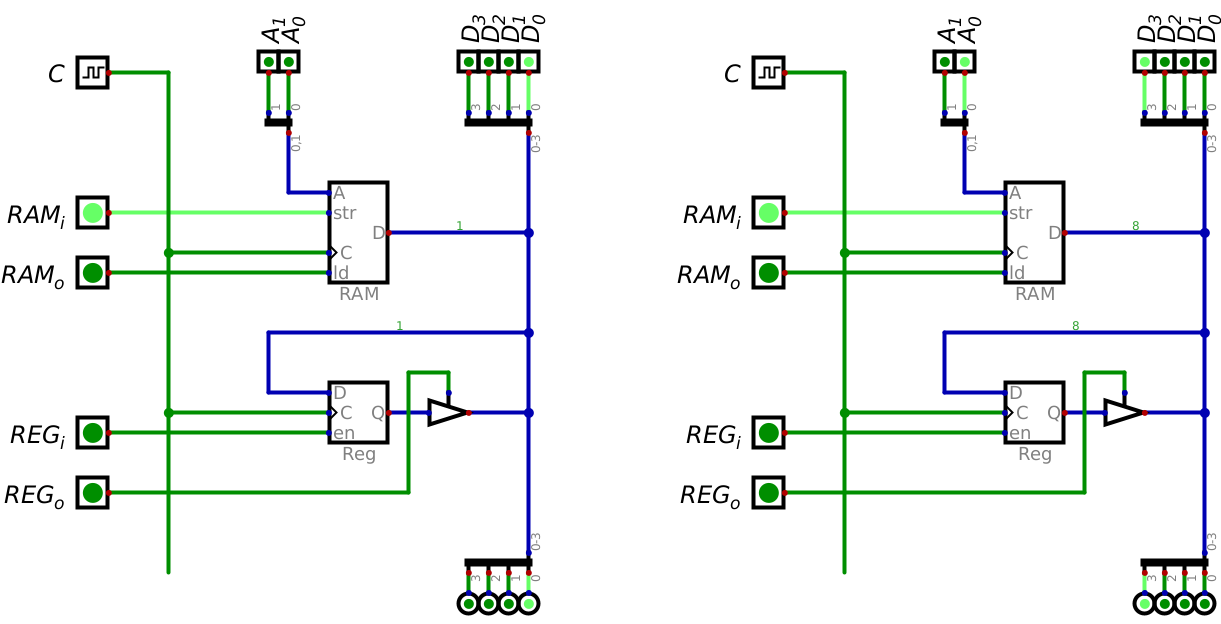

10.4. Swapping Data

Now consider a more complex problem — swap the values between the two memory addresses

Move the contents of memory address

00, which is0001to memory address01And move the contents of address

01(1000) to memory address00

Be careful to not overwrite the values in either memory address

A third, unused memory address should be used to ensure no data is lost

What would this program be?

At a high level, the solution would be

Move the value stored at memory address

00to a free address, such as10Move the value at memory address

01to00Move the value in address

10to01

However, RAM can only output or input at a clock pulse

It’s not possible to move a value between RAM addresses directly

This is where the register comes in

The register will serve as temporary storage to facilitate moving data between RAM addresses

This means the strategy to swap data would more accurately be

Move the value from memory address

00to the registerMove the value from the register to address

10Move the value at address

01to the registerMove the value from the register to address

00Move address

10's value to the registerMove the register’s value to

01

Below is a table showing the program of how the signals should be set along the busses

\(RM_{i}\) |

\(RM_{o}\) |

\(RG_{i}\) |

\(RG_{o}\) |

\(A_{1}\) |

\(A_{0}\) |

\(D_{3}\) |

\(D_{2}\) |

\(D_{1}\) |

\(D_{0}\) |

\(C\) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

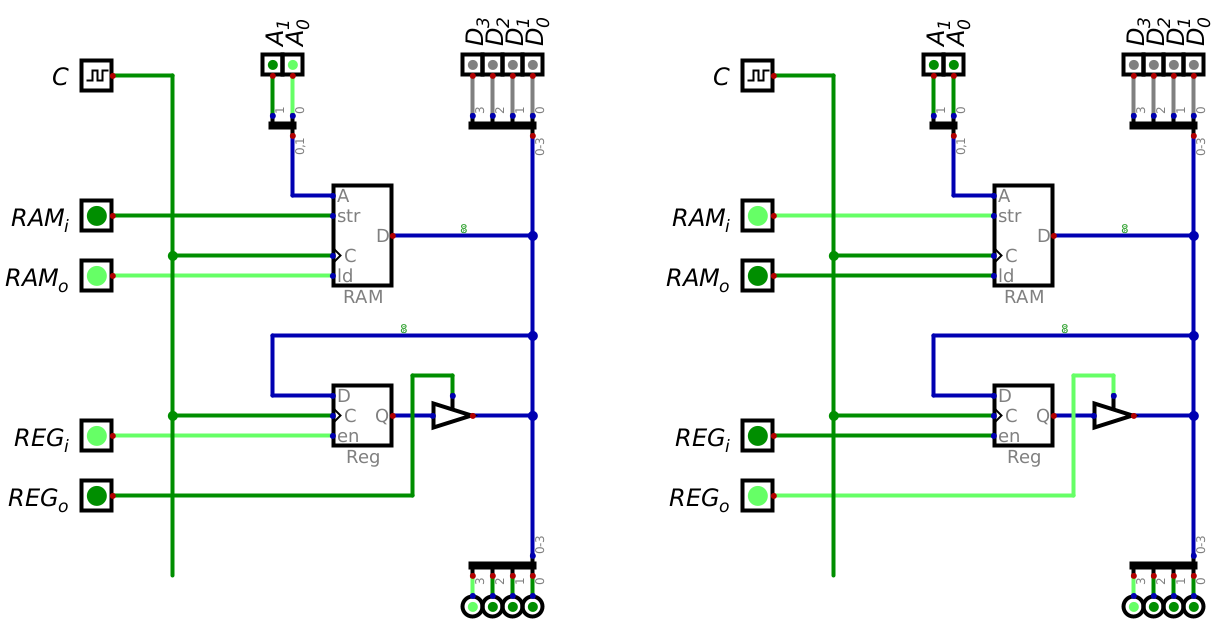

The left image shows how the signals should be set for moving the contents of memory address 00 to the register.

The right shows how they should be set to move the contents of the register to memory address 10. These two

images correspond to the first two rows in the above table.

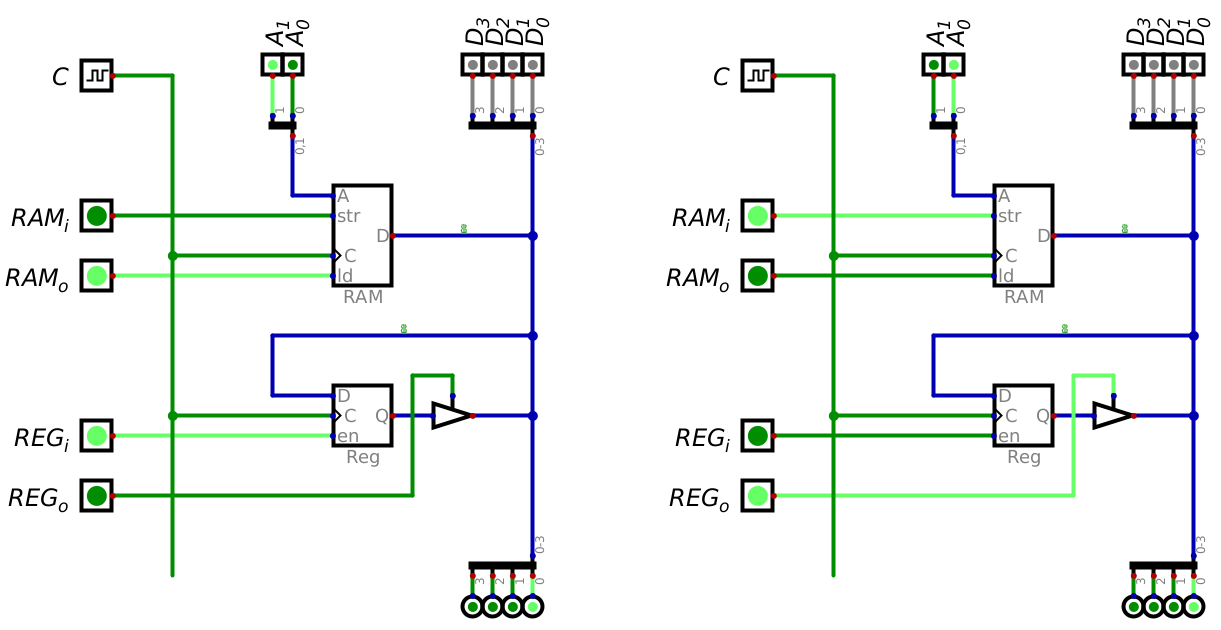

The left image shows the signals for moving the contents of memory address 01 to the register and the right

shows how to move the contents of the register to address 00. These two images correspond to the middle two

tows in the above table.

The left shows how to move the contents of address 10 to the register, and the right shows how to move the data

in the register to memory address 01. These two images correspond to the last two rows in the above table.

10.5. For Next Time

Check out the

Bus, RAM, and registerschematic for DigitalRead Chapter 2 Section 2 of your text

2 pages